Heartstopper

A summer hole dream

After being completely addicted to P-Valley last summer (an experience that still haunts me from time to time while dreaming of starting a queer pole dance group in Berlin), I lost my heart to a series again this summer. Why I fell for the british coming-of-age/coming-out series Heartstopper in just one week certainly has to do with reasons of a summer-hole-induced different leisure time behavior, but also with an interest in an aspect that I have so far paid little attention to in my exploration of queer theory and aesthetics, and which might have something to do with the renegotiation of youth under the sign of Gen Z.

Which is interesting. So, I have questions.

Probably no answers, though, since this is not meant to be a media-scientific analytical text about the series, but rather an associative commentary that revolves primarily around the question of whether we are dealing here with an asexual aesthetic that identifies gender and sexual orientation as only two facets of queer power critique, and which, in the course of, that reviews repeatedly say Heartstopper is a queer utopia,1 represents the potential of a future that is not yet, but that illuminates the horizon of our politics and our desires, as José Esteban Munoz describes it.2

That Heartstopper could be an asexual critique may at first come as a surprise, given that the story of two cis-male teenagers Charlie Spring and Nick Nelson, who fall in love with each other, is at the center of the Netflix adaptation of Alice Oseman's graphic novels. The shock falling in love (as a possible translation of "heartstopper")[5] of the two protagonists, consistently told since the first episode, visualized by means of animated comic elements of leaves and butterflies floating through the air and set to sound with crackling noises, is stretched, instead of the temporality of youthful haste, into the length of two seasons. With the help of unambiguous chapter headings, which only slightly conceal the course of life of a first love oriented to classical drama, the emotional landscape is meticulously painted with warm colors repeatedly bathed in rainbow spectral light.

Der erste Blick in Regenbogenfarben

Falling in love is told in the temporality of suspension; a time in which the smallest detail is given the greatest importance and in which the 100th kiss (and we see especially in the second season not 100, but - OMG - very many) feels like the first. The series manages to stall time and delay the grinding out of falling in love in such a way that one is hooked on love. Similar to what Nick describes in the last episode of the first season: One starts love liking.

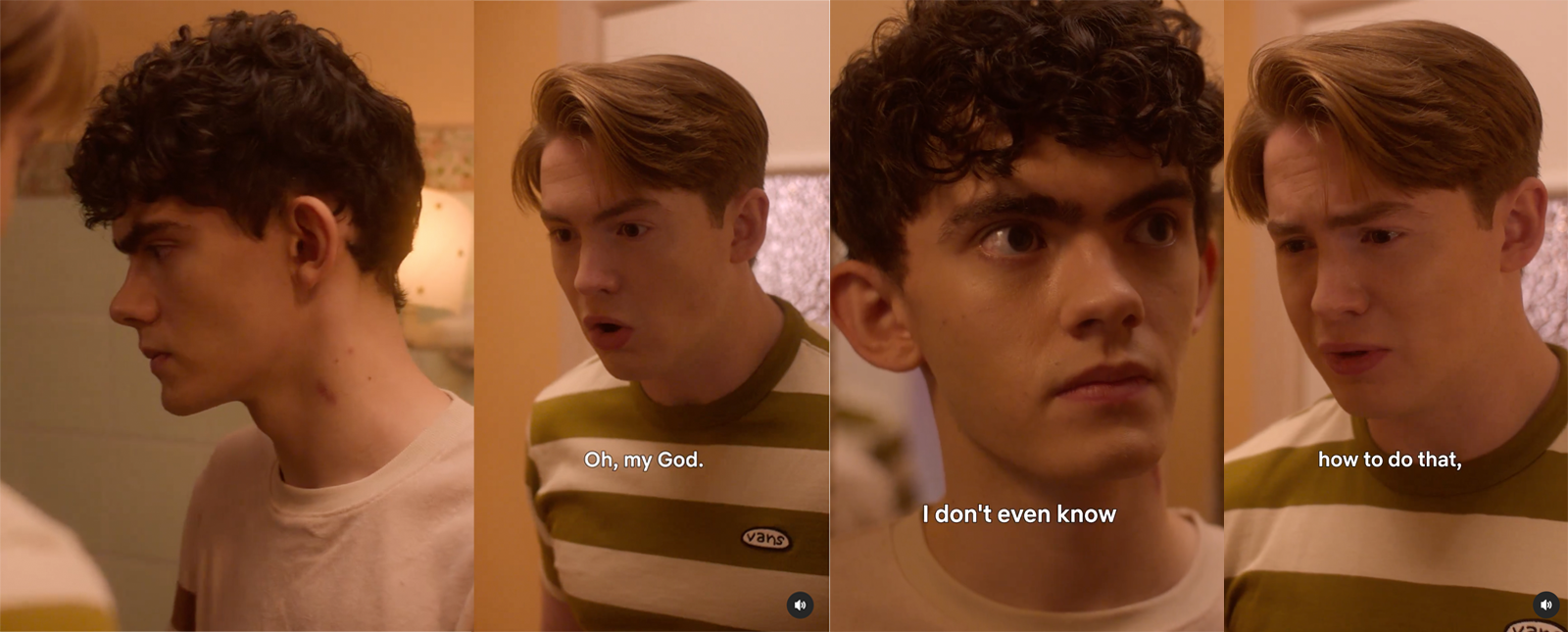

This idealization of feeling, which corresponds to the age of the protagonists, is in turn contrasted with a degree of enlightened reflection that is only assumedly associated with adulthood. Although adults appear in their role of parental responsibility, it is primarily the young people themselves who assume responsibility for one another in a downright tidy manner: Thus, it is not only Nick who protects Charlie from homophobic bullying, but it is Charlie's friend Tao who has previously stood by his best friend Elle during her transition in the extradiegetically narrated former school year. It fits with this always consensus-oriented and conflict-resolving mode of communication among the youth that, in contrast to the series Sex Education and Euphoria, in which sexuality is expressed not only discursively but explicitly as an inherent part of queer youth culture, the pleasure boundary never goes beyond the kiss, or the kiss is romanticized to such an extent that it no longer even serves as a proxy representation for sex. Compared to the sexually charged connotation of the vampire bite/kiss as it is literally celebrated in True Blood Nick's kiss on Charlie's neck ending in a hickey is also the feeling of being in love purged of arousal. The surprise of being capable of something like a hickey at all attests to the notion of intimacy freed from sexual desire.

Oh, my God, es ist ein Knutschfleck

At the points where desire does come into play, the scene is either interrupted or sidestepped into inauthentic speech of suggestion ("I didn't think we'd do ... that right now.", "I do... I do want to"). As distinguished as emotional states and fears are exchanged, speaking about queer, gay sex or bisexual desire remains a blank space or a code that - at least for me (generationally?) - can hardly be deciphered.

Admittedly: This leaves me somewhat perplexed, simply because in the course of my engagement with queer theory I have been much concerned with gay sex and queer desire in terms of an affective potential for transgression of normative expectations about bodies and mental health, and I find intimacy important as a critical site of negotiation of social notions of family and reproduction. At the same time, I can't help but think of Heather Love's engagement with the spinster as a queer figure.3 This literary figure draws attention to loneliness and impossibility as lived experience due to the hostility of society. It thus functions as an analytical burning glass for societal maladjustment. As a cinematic character, it is also central to the film Moonlight. Loneliness and sexual abstinence of Black gay masculinity refer to racism and toxic masculinity culture in Black communities. This means that an idealization of cis-masculinity, heterosexuality, and familiality has emerged in Black communities in response to the dehumanizing and demeaning experience of racism. The tragedy of the protagonist Chiron is that the impossibility of existing as a Black gay man is compensated for with hyper-masculinization and violence.

This compensation can be observed – as a follow-up to P-Valley, my "heartstopper" moment in 2022 – regarding the actor J Alphonse Nicholson. It seems to me that as a result of his role as Lil Murda, a Black gangsta rapper who falls in love with Uncle Clifford, the Black gender-bending gay owner of the Pussy Valley pole dance club, he consciously/unconsciously felt compelled to overemphasize that he was straight and a father. The large staged wedding photos can be understood as a culmination of wanting to close the possibility space, he could be gay himself. Kit Connor, the actor who embodies Nick Nelson in Heartstopper, the boy who comes out as bisexual, in turn seems to want to compensate for the pressure – created by a by now obviously toxic fan culture – not with the invocation of heterosexuality, but with an embodiment of a certain, namely muscle-defending image of masculinity.

Without slipping too deeply into remotely diagnostic psychograms of actors I don't know any further, I think that – and here I'm trying to find a connection to my question – Heartstopper is a representation of asexual gay masculinity in the sense of a critique of precisely those social conditions that cause people to behave according to supposed expectations. In this respect, the shy expression of gay/bisexual desire can be understood as an attempt to translate feelings of social rejection into a moment of romantic affection. Perhaps, given virulent incel cultures that do the opposite and reformat (sexual) rejection into (misogynistic) hatred, this is indeed a queer utopia. A queer utopia that still has some catching up to do in terms of intersectionality, since – although Black protagonists are part of the set – racism does not play a role and disability also only serves to diversify, but not to challenge rejectionism in schools, for example, especially in art schools. It is thus confusing that it is Felix, who sits in a wheelchair, of all people says in the second season that art schools are a better place, among other things because of party.

Well, I can relate to that.

And yet, in the course of the discussion about the abuse of power, especially at art academies, and above all because of the blurring of the boundaries between educational mediation and party, we know about the fragility of these spaces, which mostly works to the disadvantage of marginalized people. In turn, the series discusses that this is the case. Thus, it is not the parties that are the queer heterotopias, but the sideshows. It is not on the dance floor that the narrative between Charlie and Nick is advanced, but in the side room. In order to get closer to each other, they don't need the spotlight of the big stage. In the small space next to it, the essential happens for the queer story.4 Not to step out of this small space is no loss for queer love and queer utopia.

So, stay put becoming minor.

At least until the release of the fourth season of Sex Education. Wink wink.

- 1Shirley Li: Heartstopper and the Era of Feel-Good, Queer-Teen Romances, in: The Atlantic, 11.5.2022, https://www.theatlantic.com/culture/archive/2022/05/heartstopper-netflix-love-victor-coming-out/629827/; Xualin Tham: Heartstopper season 2 smartly shatters the show's utopian vision of growing up queer, in: British GQ, 2.8.2023, https://www.gq-magazine.co.uk/article/heartstopper-season-2-shatters-queer-utopia.

- 2José Esteban Muñoz: Cruising Utopia. The Then and There of Queer Futurity, New York, London 2019, 1.

- 3Heather Love: Feeling Backwards: Loss and the Politics of Queer History, Cambridge, London 2007.

- 4Gilles Deleuze: Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature, Minneapolis 1986.

Bevorzugte Zitationsweise

Die Open-Access-Veröffentlichung erfolgt unter der Creative Commons-Lizenz CC BY-SA 4.0 DE.