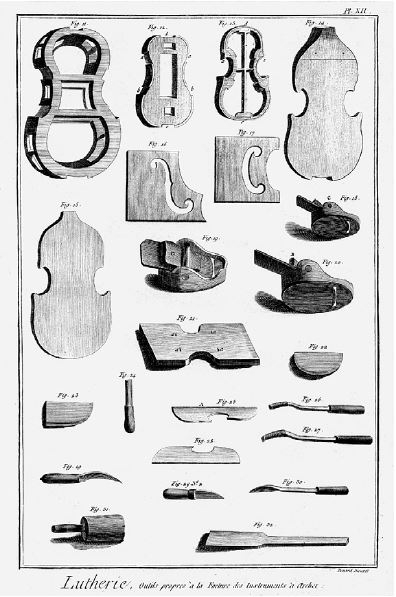

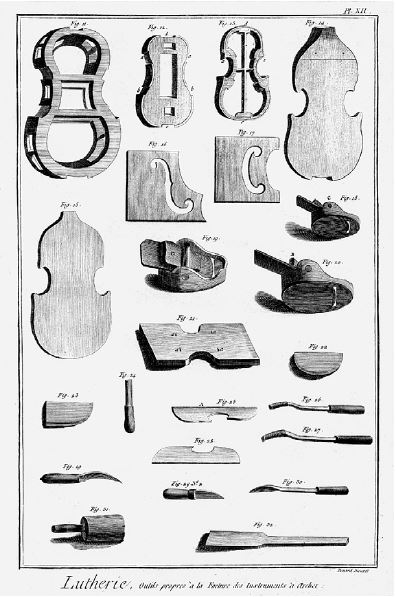

«Der Geigenbau» (detail), plate XXII from Denis Diderot's «Enzyklopädie», 1762–1777

An Ecology of Materials

An Email-Interview on Correspondence, Resonance and Obsession, and on the Benefit of Combining Scholarship and Craftsmanship

The German version of this text was published in Zeitschrift für Medienwissenschaft, No. 14, 2016. Deutschsprachige Version dieses Beitrags hier.

For some time, ecological questions have become important in anthropology, as Tim Ingold’s writings show. His ideas on the potential of organic and anorganic materials, their compositions and decompositions, also arouses the interest of media studies – maybe because it questions the exclusiveness of human agency. Making, in Ingold’s conception, is a process in which different materials unfold their potentials. For a mediaecological perspective, materials grasped in this way offer the chance to understand technical media not as passive, invariable tools used for a purpose, but as instable and active assemblages of matter with their own potentials of activity. In our interview, Ingold elaborates upon his position in an ecological anthropology that values the becoming of things and is interested in the circulation of materials and their amalgamation. Furthermore, he argues for a reconciliation of scholarship and craftsmanship – in other words, for a praxeology of thinking and making.

Petra Löffler, Florian Sprenger: Let's start by referring to your latest work. In your recent articles and books you develop the concept of an «ecology of materials» and focus especially on material activities which are co-composing the world.1 Furthermore, you argue that from the point of view of ecological anthropology, these materials have to be considered in a symmetrical approach, in other words, that we should analyze organic as well as inorganic modes of existence. This perspective implies three basic shifts: from things to material flows of energy, from Aristotelian hylomorphism to a manifold of formative processes, and from ontology to ontogenesis. Based on the techno-philosophy of Gilbert Simondon on the one hand and Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari‘s seminal book Milles plateaux on the other, you maintain that materials act in special ways regarding their elasticity or resistance, their conformations or deformations. As media scholars, we are interested in how this approach can help us to understand the recent shift in focus from media as instruments, apparatuses or tools – in short: from media as formed matter to assemblages of different materials with different life times. Following this line of thought, what changes occur when you consider technical media or technologies as beings under permanent construction, deconstruction and reconstruction? What are the special characteristics of the materials involved in those processes? What is at stake in speaking of materials instead of matter or substance?

Tim Ingold: What you say in summary of my most recent work is absolutely correct, with perhaps the one qualification that what is often portrayed in the literature as a «symmetrical» approach (after Latour) is one of which I am actually critical. This is for the reason you state, namely that it rests on the profoundly asymmetrical foundation of a human exceptionalism that leads to «things» not being considered as beings in their own right, but only in so far as they are enrolled in human projects.

But your question is a difficult one. I have been trying to think about it in terms of my cello (and you can find the beginnings of an answer in chapter 21 of my book The Life of Lines entitled «Line and Sound»). The thing is that in an earlier book (Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture, Chapter 7, «Bodies on the Run») I described the cello as a transducer, which serves to convert the movement or flow of the gesture from one register, of bodily kinaesthesia, to another (in this case) of sound. Thus the instrument slides along, between the two lines – of gesture and sound – but while the lines unfold and go in all the varied ways they do, the instrument itself remains pretty much the same, coming out at the end of the performance in virtually the same condition as at the beginning. But in writing The Life of Lines, I realised that this is only one part of the picture. The other part is that when I begin to play, the instrument no longer feels like an «instrument» at all. Rather it feels like a bundle of materials – wood, bow hair, metal, rosin and air –– that seems literally to explode as I begin to play, blasting off into the immensity of auditory space. It is, as you put it in your question, in a permanent state of deconstruction and reconstruction. When I play, then, I am not so much playing an instrument as mixing the materials (elasticities, flows, frictions, etc.) of my own body with the wood, rosin, metal, hair and the resonant air. All of these are affects of a kind.

So which picture is right? I don‘t know. Perhaps they both are, but I’m not yet sure how to combine them. I don’t know whether this makes any sense, but it is the best I can do just now.

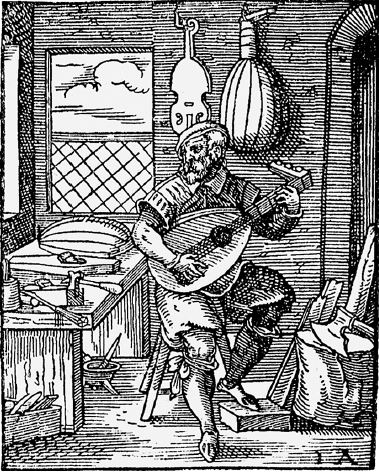

«Der Lautenmacher» by Jost Amman, woodcut, 1568

P.L./ F.S. To us it seems that in the first picture the cello is described as a resonating body without an agency of its own, whereas in the second picture the relationship between you as human agent and the cello as non-human agent is more complex and interdependent – just flows of energies and materials. This mixing or interfusion of materials includes solids such as wood or metal as well as less solid materials (semi-fluids or the air). How do these very different materials (regarding their solidity or ductility) interact in concrete ways? Is, for instance, wood a less active material than, let’s say, rosin or bow hair? Or is metal less vivid than resonating air? In other words: In which ways do these different materials contribute to an ecology of materials?

T.I. Personally, I dislike the concept of agency (though I have nothing against «action» or «activity»). The problem with agency is that it makes it sound as though every going on in the world - every movement, every happening, every occurrence - is merely the effect of a cause. «I move, therefore it is an effect of my agency». But to my way of thinking, I am inside what I do, inside the verb, not outside of it and causing it to happen. So to recapture the vitality of things, rather than following people like Jane Bennett2 in granting the things the same «agency» that we would grant to people, I would rather go the other way and say that neither people nor things «possess» agency. Rather, they are equally «possessed» by the action.

Having got that out of the way, I can agree that the difference between these two views of the cello is precisely this, that in the first the vitality of the materials that comprise it doesn’t really enter the picture, whereas in the second it completely takes over. The materials, as it were, overwhelm the thing. The advantage of this second perspective is that it allows us to start asking questions about the properties of materials (rather than about the materiality of things). And this, as you say, opens the way to an ecology of materials.

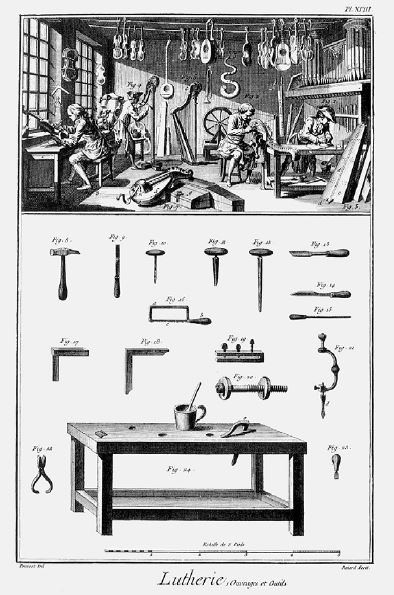

«Der Geigenbau», plate XXII from Denis Diderot's Enzyklopädie», 1762–1777

Concretely, to discover the properties of wood, hair, rosin and the rest (I forgot to mention varnish, too, which is absolutely critical for the tone of the instrument) would require an investigation in itself. But I don’t think the answers can be given in terms of «more» or «less» of this or that. It is about differences and about how they work together or correspond. Just for example, the (soft) wood used for the front of the cello is quite different from the (hard) wood used for the back, and the grain goes in different directions. There are good reasons for this, which have to do with sensitivity to vibration in one case and tensile strength in the other. Then again, metal strings have quite different properties from strings made of gut – which I started on but have more or less disappeared these days. Players say that the quality of metal strings declines in use, but with gut it increases. I think it was Pablo Casals who said that a gut string never sounds better than when it is just about to break! These sorts of observations, which in the past might have been dismissed as «merely technical», would be absolutely central to an ecology of materials. We could at last take the know-how of instrument-makers and players seriously. More than that, treating the instrument as a body that lives and breathes – that is animate (rather than an agent) – allows us to look at how it responds to the conditions of the wider environment, most particularly the weather and the humidity of the air. I know for a fact that my cello never sounds better than when it is really damp. If there is one thing it hates, it is central heating. Makers of fine wooden furniture, I think, say the same about their work.

«Der Geigenbau», plate XVIII from Denis Diderot's «Enzyklopädie», 1762–1777

P.L./ F.S. Ecology was one of the first fields of research to reflect upon the position of the observer, because every observer stands in systemic correspondence to the system he observes. An ecologist investigating the ecosystem of a pond changes the conditions of the pond by investigating it. In this regard, ecology resembles ethnography and anthropology. In your work, you underline the responsibility of the observer, his ethical involvement with the objects of his interest. Would you say that ecology is an ethical approach to materials?

T.I. Yes, ecology can and should entail an ethical stance. We are an intrinsic part of the systems we study. To me that is self-evident. It is a fact, however, that much research that goes under the banner of «ecology» does not take such a stance. I think it would be fair to say that in the scientific mainstream, ecology is still premised on a fundamental (and unaddressed) division between universal humanity and natural biodiversity, as if we humans were looking at (or intervening in) nature from without. We need to change this, and anthropology – with its practice of participant observation (not to be confused with «ethnography») – can point the way. But this means, too, that we should recognise in participant observation not just a technique for collecting qualitative data but a fundamental ontological commitment (this argument is spelled out at greater length in the first chapter of Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture).

P.L./ F.S. In your paper «Materials against Materiality»3, you argue that studies of material culture tend to disregard materials: often they have hardly anything to say about them. Instead they confine themselves to abstraction and refer to the «materiality of objects» instead of «materials and their properties». How can materials inform scholarly investigation? How do you access the «silent world» of materials, and what is the role of the observer in this process of engagement?

T.I. First, it is interesting that you should say that materials are «silent» (albeit in scare quotes). Of course they can make a lot of noise, even musical noise – back to my cello! You could ask, if the materials of my cello are silent, where is all that sound coming from? Maybe the point is that materials do not communicate by means of speech. But then the same could be said of (most) non-human animals. So there seems to be a strongly anthropocentric cast to the idea that materials present a problem when it comes to access and engagement. There is of course a very long answer to the question of how and why the world of materials came to be silenced in the history of modernity, and it is not unconnected to the silencing of the word in the history of writing, and to the modern idea of music as wordless sound (some of this is told in the first chapter of my book The Life of Lines, and some in my article «Dreaming of Dragons» – which I attach in case you haven’t seen it). However the short answer to the question of how to access materials is to engage with them in straightforward, practical ways. Or in a word, it is to attend to them. This kind of attentional (rather than intentional) engagement has been practised by craftsmen for generations. So what we need to do – and in many ways this is already happening – is to close the gap between craftsmanship and scholarship, to see them as one and the same.

P.L./ F.S. We would also like to come back to your critique of Bruno Latour: In your article «Towards an Ecology of Materials» you criticize his approach for failing as ecology because his nonhuman agents are inanimate, lacking any trail of movement, of growth, of perception or resonance. To highlight such trails you speak of a meshwork instead of a network. Our question is: what forces hold this meshwork together?

T.I. The short answer to your question of how the lines of the meshwork hang together is through what I have called «correspondence». This is a going-along-together of flows or «becomings» that are continually answering to one another. For me the obvious analogy is with the lines or «parts» of polyphonic music. I think I referred to this earlier.

So the two key words, in answer to both questions, are «attention» and «correspondence». Together, they are absolutely central to what I am working on now.

P.L./ F.S. You mentioned the importance of craftsmanship as a role model for an ecology of materials. How does this perspective correspond to our current technological condition? Today, we are confronted with ubiquitous and smart technologies, with a «technological unconscious», that is, with technologies that interact with our environments without our active participation, that decide below the thresholds of our sensibility. Some of these machines are even created by other machines – the construction of computer chips for example is in its whole accomplished by computers and computerized machines. Most of the processor units in our gadgets and devices are never touched by a human finger. How do we engage with these technologies? How can we include them in our ecologies of materials? One could think that the reference to craftsmanship is a turn away from such technologies. But perhaps your approach can lead us to a different conception of such technologies?

T.I. When it comes to digital technologies, I tend to defer to others who have more knowledge of such matters. It is all I can do to operate a keyboard. Personally, I feel profoundly uncomfortable with the «digitisation of everything». The loss of the skills of handwriting, for example, seems to me a tragedy as great as if – in some imagined future – there was no more song in the world. Handwritten lines sing, word-processed lines do not. A whole register of feeling is eliminated. People say that I am nostalgic, but if the opposite is a world without feeling, then I’m for nostalgia! However, I suppose there is no reason why digital technologies should be at the expense of feeling. If, instead of developing keyboards to replace the hand in writing, we put our energies into developing a digitally enhanced pen that would actually increase our sensitivity to the nuances of the line or the qualities of the paper surface, then we could perhaps get the best of both worlds. Indeed I believe such developments are already happening. But I am not well-informed about them.

Perhaps what is required is a rethinking of the term «smart». In conventional usage it has a distinctly neoliberal, entrepreneurial and competitive ring – the sort that equates creativity with innovation. It is imbued with the logic of commodity capitalism. But if smartness could be realigned with attentiveness and correspondence, with care and sensitivity for the people and things around us, then perhaps smart technologies could have their place in an ecology of materials.

I felt this very strongly during a conference I attended at the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts in Maine last July. There was a real tension between those who were excited by the potential of digitally enhanced technologies, including 3-D printing, to deliver innovative and possibly market-leading solutions to global problems in fields such as public health and environmental change, and those whose focus was entirely on the way in which a slow, intimate and intense engagement with materials could bring about an almost spiritual kind of personal salvation. These are extremes of course, but most participants found themselves somewhere in between them, and pulled in both directions.

P.L./ F.S. To come to an end, we would like to draw a line from these technologies to ecology. Your answers make clear, at least for us, that media ecology has to include engagement with all environmental forces, with animate as well as inanimate entities. But the question remains whether your plea for attentiveness does not at least imply an anthropocentric attitude towards materials? In other words: In which ways are materials attentive to themselves?

T.I. There are two possible answers to this question:

The first: Of course, materials are attentive to one another, just as humans are attentive to materials. Materials can get up to all kinds of things behind human backs and without their knowing, often to disastrous effect. Engineers, materials scientists and ecologists have always known this. That’s why the claim of the so-called «object-oriented ontologists» to have come up with a revolutionary, non-anthropocentric philosophy – as though it were some great new discovery – is so ludicrous. I wonder where they have been all these years? Probably reading far too much philosophy and not enough ecology.

The second: Attention calls for perception and action. Therefore you can only reasonably talk about attention on the part of organisms endowed with nervous systems. That includes all animals, and not just humans. But it doesn’t include inanimate materials. A tiny insect may weigh no more than a grain of sand, but there is a fundamental difference between them in that the insect can attend to things but the sand-grain cannot.

To be honest, I don’t know which of these two answers is right. But either way, humans do not have to be at the centre of things.

- 1See Tim Ingold: Being Alive. Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description, London 2011; Towards an Ecology of Materials, in: The Annual Review of Anthropology, Vol. 41, 2012, 427–442; Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture, London 2013; The Life of Lines, Abingdon 2015.

- 2Tim Ingold makes reference to Jane Bennett's book Vibrant Matter. A Political Ecology of Things (Durham, London 2010)

- 3Tim Ingold: Materials against Materiality, in: Archaeological Dialogues, Vol. 14, No. 1, 2007, 1–16.

Bevorzugte Zitationsweise

Die Open-Access-Veröffentlichung erfolgt unter der Creative Commons-Lizenz CC BY-SA 4.0 DE.