Still aus David Lynch Presents William Blake’s “The Sea of Time and Space” (2025), Jacob Smith

David Lynch Presents William Blake's The Sea of Time and Space

David Lynch is best known as a film director, but he got his start as a painter. In interviews, Lynch has often mentioned two artists as influences: Francis Bacon and Edward Hopper.1 To my knowledge, Lynch has never discussed William Blake as an influence, which is somewhat surprising since they have much in common. Their work shares a number of themes: the comingling of contraries such as good and evil, light and dark, heaven and hell; an interest in expressing those contraries in terms of sexuality and the depiction of what Blake calls «naked beauty;» the creation of sprawling personal mythologies from the Four Zoas to the multiple universes of Twin Peaks; and a tendency to merge cosmic scales with the very small, be that the world in a grain of sand or paradise in a damn fine cup of coffee. Their careers as working artists also bear some notable similarities: both are multimedia artists who work in popular forms (either printing or television), and embody a maverick or outsider position in relation to their art world.2 To explore the resonance between these two artists I have created an audiovisual essay that combines images from Blake’s painting The Sea of Time and Space (1821) with sounds created by Lynch and his collaborators, Alan Splet and Ann Kroeber.

Part of my motivation for this project is to better understand visionary art. L. Caruana asserts that visionary art is a mode of creation that is guided by the desire to «bear witness to other realities» as made evident in «alternative states of consciousness.»3 For Alex Grey, visionary art is based on personal experience of the divine and an attempt to make inner truths sensible via «an external material-world manifestation.».4 Carl Jung describes the visionary mode of artistic creation as one that goes beyond the «realm of the understandable» and that exceeds «the grasp of human feeling and comprehension.»5 Blake is often mentioned as a paradigmatic example of a visionary artist, and he himself asserted that «Vision or imagination is a Representation of what Eternally Exists, Really & Unchangeably … the Nature of my Work is Visionary and Imaginative.»6

Eraserhead (1976) provides a good case study for considering the visionary status of Lynch’s work because it has frequently been interpreted in spiritual terms; specifically, in relation to a Gnostic system of thought. Eric G. Wilson argues that several of Lynch’s films present themes that resonate with a Gnostic tradition that focuses on the raw experience of the divine.7 For Wilson, Eraserhead is a «retelling of the basic Gnostic myth of the fall» since the film’s protagonist descends from an «ethereal realm above space and time» into a mundane reality that seems to be controlled by a «wounded demiurge,» the mysterious Man in the Planet.8 In a recent study, Claire Henry takes Gnosticism as a template for interpreting the film and refers to Lynch’s claim in 2006 that Eraserhead was his «most spiritual movie» and moreover, that a particular Bible passage, which he would not reveal, was a key that unlocked certain sequences. For Henry, Lynch’s statements validate taking a mystical approach to the film via a Gnostic framework.9 Eraserhead's mysterious spiritual overtones make it a fitting companion to Blake.

Eraserhead also provides a formal means by which these two artists might be brought into dialogue given that it is famous for its remarkable soundtrack. In fact, if Blake offers an underutilized approach to Lynch, sound offers an underutilized approach to Blake. Celebrated as a poet and visual artist, the sonic dimension of Blake’s work has received less attention, despite reports of him singing his poems and multiple musical settings of his verses. Apart from these musical adaptations, there have not been sonic engagements with Blake that mobilize the full possibilities of non-musical audio, sound art, and sound design. Inspired by initiatives such as the ‹Soundscapes› project at the National Gallery in London, which commissioned musicians and sound artists to compose new works of audio for a specific painting, I decided to pair a Blake painting with a Lynchian soundtrack.10 Working in the genre of the scholarly videographic essay, I have created a cinematic adaptation of Blake’s The Sea of Time and Space featuring Lynch’s signature approach to sound.

What is Lynch’s signature approach to sound design? Michel Chion compares the Eraserhead soundtrack to a work of musique concrète and describes its «uninterrupted sound-atmosphere» periodically punctuated by «brutal and instantaneous cuts.»11 Eraserhead features a dense layer of ambient sound comprised of industrial and atmospheric sounds, which envelops the audience. «The noise of the machine, its micro-activity of particles, places us in a secure inner space like some bodily machinery,» Chion writes. «With sounds in Lynch’s work, we are constantly within something.»12 Exactly what we are within is not always clear however, and sound design in Eraserhead gives us the disconcerting sense of being nested within multiple worlds, ranging from the inner consciousness of the protagonist to the lived environment, and outward to vast, cosmic spaces.

Commentators like Chion tend to talk about this as Lynch’s personal sonic signature, but the soundtrack to Eraserhead was created in collaboration with the legendary sound designer Alan Splet, who worked closely with Lynch on all his films from The Grandmother (1970) to Blue Velvet (1986). Splet also worked on Carroll Ballard’s The Black Stallion (1979) and Never Cry Wolf (1983), as well as films by Peter Weir and Philip Kaufman. Splet died in 1994, and his sound design partner and wife, Ann Kroeber, continued to manage the sound library that they had co-created. This sound effects library, the Sound Mountain collection, was sold to the Pro Sound Effects company in 2017.13 I purchased the Sound Mountain collection and have used it exclusively throughout this videographic essay. The result is that my video is not only suggestive of Eraserhead, or made in the style of Lynch and Splet: it is made from the very same archive of sounds.

It is a videographic mashup in which Lynch is represented by the Sound Mountain collection and Blake is represented by The Sea of Time and Space. I chose the latter for several reasons. First, the image has a dynamic sense of circular movement suggestive of narrative development in time, which I have animated through editing. Second, it presents figures, scenes, and themes that fit well with the recordings in the Sound Mountain archive. Third, The Sea of Time and Space has been the subject of a rich Neoplatonic line of interpretation that rhymes with the Gnostic overtones of Eraserhead outlined above. The Neoplatonic interpretation of the painting comes from the poet and scholar Kathleen Raine, who presented her argument in articles and books, most notably Blake and Tradition (1968). The rest of this essay presents Raine’s reading of Blake’s painting as a guide to my video.

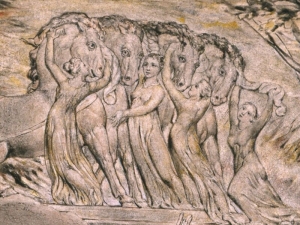

The Sea of Time and Space depicts the mysterious «cave of nymphs» passage in Book 13 of Homer’s The Odyssey.14[Figure 1] Raine argues that Blake’s work is best understood in relation to an interpretation of that passage that can be found in works by the third century philosopher Porphyry and the English Neoplatonist Thomas Taylor. Raine states that The Sea of Time and Space is, in fact, Blake’s representation of «the essentials of Neoplatonism, of the descent and return of souls, of the crossing of the sea of time and space.».15 Indeed, the painting depicts a traditional aspect of Neoplatonic and Hermetic symbolism: Odysseus as an emblem of the journey of life across «the stormy and unstable sea of material existence.»16 The video begins in the flux of material existence as embodied by waves on the sea. [Figure 2] From there we meet Odysseus, just landed on the beach near his home, midway through life’s adventure, silhouetted against the tempest-tossed sea. [Figure 3]

(Fig. 1-3)

Odysseus is depicted in the act of throwing a scarf out to sea, which he was given earlier in the story by the goddess Leucothea.17 Leucothea told him: «When you reach dry earth, untie the scarf/ and throw it out to sea, away from land,/ and turn away.»18 It is this act of throwing while turning away that Blake represents in Odysseus’ bi-directional posture.19 Out in the turbulent waters, we see Leucothea being drawn by four horses, which likely correspond to Blake’s Four Zoas; the four fundamental aspects of the human condition.20 [Figure 4] The presence of these horses motivates the use of several horse recordings from the Sound Mountain collection, most of which were created for the film The Black Stallion. The scarf thrown by Odysseus is being transformed into a cloud, and given that Blake often used clouds and garments as symbols for the physical body, we are seeing Odysseus throwing off his material embodiment like an old garment at the end of his life’s journey.21 Airy sounds animate the scarf as it transforms into a cloud, and we move upwards to a glowing sun chariot and a host of celestial beings. [Figure 5]

(Fig. 4 and 5)

The chariot of the sun is driven by another set of four horses and is surrounded by «bright ascending souls» and «radiant spirits,» several of whom hold musical instruments.22 [Figure 6]The music for this sequence is comprised of a chorus of wolf howls from the Sound Mountain collection (recorded for the film Never Cry Wolf), and a subtle hint of the Fats Waller organ music that accompanies the «Lady in the Radiator» sequence in Eraserhead.23 The heavenly, celestial realm of the painting is thus linked with an analogous space in the film: the stage where the Lady in the Radiator performs. Godwin describes the Lady’s «stiff little Shirley Temple-like dance» as «sperm-things» drop on the floor around her: «She steps around them daintily with a coy smile until the music stops; she steps on one of the things and it squishes a milky fluid out on to the stage.» Godwin concludes that this is the protagonist’s definition of Heaven: «A warm, moist, safe, enclosed place: the womb. But a sterile womb. Its sexless inhabitant and guardian eliminates the intruding sperm, thus guaranteeing that no conception will occur – and so no birth, no entry into the hated outer world.»24

(Fig. 6)

The Blake painting continues towards a re-entry into the outer world however, and having completed the upward movement from Leucothea to the sun chariot, we embark on a lateral movement to the right, where we find the chariot’s four horses being attended by female figures. [Figure 7] The lateral movement brings us to a region of trees and a brief pastoral interlude. [Figure 8] From here we begin a vertical movement downwards, descending into the cave that is the heart of the Homeric passage that has accrued so much Neoplatonic commentary. Homer describes the harbor of the sea god Phorcys as being near a «beautiful dark cave,/ a holy place of sea-nymphs – Nereids./ Inside are bowls and amphorae of stone,/ and buzzing bees bring honey. There are looms,/ also of stone; and the Nymphs weave purple cloth,/ sea-purple – it is marvelous to see. There are/ two entrances. The north one is for humans;/ the south is sacred. People cannot enter/ that way – it is the path of the immortals.»25

(Fig. 7 and 8)

Raine, following Taylor, writes that caves have long been sacred places that embody the mysteries of a passive into and out of life. «The secret of the Cave of the Nymphs,» she writes, «is related to the mysteries of the identity of womb and tomb.»26 The souls descending into generation are represented by buzzing bees who deposit their honey in the bowls and amphorae of stone, which Blake represents as womb-like urns being carried on the heads of winged nymphs.27 [Figure 9] Bees were a symbol for returning souls because they were known to return to their hives across long distances.28 On the soundtrack, the sounds of buzzing insects come from Sound Mountain recordings made for the film, The Mosquito Coast (1986).

(Fig. 9)

Descending a stairway into the lower depths of the cave we encounter nymphs working at a loom. [Figure 10] In the Neoplatonic system of interpretation, these are the looms of generation, where bee-like souls are given bodies of flesh and bone as they descend into the material world. The stone looms are the bones on which the purple cloth of the flesh will be woven. Raine suggest that the little girl on the right of the loom in Blake’s painting is «enmeshed in what the three nymphs are weaving. Perhaps Blake here intends to represent the process of generation.»29 [Figure 11] On the soundtrack, the loom is accompanied by the rattle of machinery and the process of embodiment is represented by Lynchian sparks of electricity.

(Fig. 10 and 11)

The video’s descending movement returns, following a stairway and the trunks of four large trees that span the image from top to bottom. Movement along the trunks of these impressive trees leads to the roots, which are submerged in the dark waters along the bottom of the image. Raine writes that, with their roots in the water and their crowns reaching to «the golden country above the cave,» these trees suggest that «the roots of life are in the lower world, its leaves in eternity.»30 Moving closer to the roots submerges us in the water, and introduces a new watery soundscape.31 [Figure 12] The sounds of water are well-represented in the Sound Mountain collection and water is an important symbol in Neoplatonic cosmology. Raine explains how, in the Neoplatonic view, souls descending into generation are drawn to moisture and become corporealized by condensing into a «humid vehicle like a cloud.» An incarnating «moist soul» is seen in the bottom right corner of the painting, half-immersed in the water, and «sunk into a blissful sleep of Lethean forgetfulness.»32[Figure 13]

(Fig. 12 and 13)

Now we begin a lateral movement to the left along the bottom of the image, moving with the river of life as it moves through secret depths and runs out to sea.33 Sound Mountain recordings provide a crescendo of water that moves from drips to a trickling stream to a river that meets the thunderous surf. The soundtrack builds in intensity as we are swept along this current, past a group of figures who represent the sea god Phorcys and the Three Fates. The Fates are unspooling a thread from the loom, which suggest an umbilical cord. [Figure 14] In the bottom left of the image, one of the Fates holds a pair of scissors.34 As the soundtrack’s watery crescendo reaches its peak, we center on the scissors and snipping sounds mark the moment of birth as the soul returns to the sea of time and space. [Figure 15] The soundtrack abruptly cuts to silence followed by the cries of an infant, suggesting a birth in a manner that is meant to recall Lynch and Splet’s famous sound design during the prologue of The Elephant Man (1980).

(Fig. 14 and 15)

After this dramatic moment of birth/rebirth, we return to the ocean waves where we began, and then once more to Odysseus on the shores of Ithaca. However, this time we follow the other direction indicated by his bifurcated posture, moving in the direction of his gaze and, perhaps more importantly, of his outstretched foot, which is making contact with a figure standing behind him. This is the goddess Athena, the embodiment of Divine Wisdom. [Figure 16] Raine writes that the three main figures at the center of the painting, Odysseus, Leucothea, and Athena, suggest a single circling rhythm centered on Odysseus himself.35 I have narrativized this circling pattern by following first his arms and then his face, but Blake seems to suggest that these two movements co-exist; that it is not one and then the other, but both simultaneously. In Raine’s words, we are shown a «ceaseless round of death and rebirth» in the painting’s «circling or spiraling rhythms.»36

(Fig. 16)

Once we have encountered Athena, the video makes a final ascent, following Athena’s uplifted arm, which directs Odysseus’ attention to the heavenly sun. [Figure 17] If the throwing of the scarf symbolizes the death of the material body and the descent through the looms of generation is birth, here we find a third option: the visionary glimpse of Eternity in life: an artistic representation of «what Eternally Exists, Really & Unchangeably.»37 The video does not end here however, but continues to a final sequence that connects two figures in the image, both sleepers. The first is the sun-god, who is «sunk in profound sleep.».38 The second is the «moist soul» in the depths of the cavern, not yet awake to life. [Figure 18, 19] Raine writes of the sleeping sun-god:

Blake is suggesting the contrasting states, of life in this world as death in the other; or, in this case, the waking of the one as the sleep of the other. Modern psychologists would say that the waking of consciousness is the sleep of the unconscious – and indeed this whole theme would as readily lend itself to a psychological as to a metaphysical interpretation. Below, all is wakeful energy and action; in the world of the immortals, there is profound sleep.39

Odysseus then, is at the center of two circles: one with Leucothea and Athena at its circumference; and the other with these two sleepers, representing two states of unconsciousness, at its circumference.

(Fig. 17-19)

I found the work of synchronizing Lynch’s audio with Blake’s image to be illuminating in several regards. Lynch and Splet’s sound palette is notable for its emotional power and complexity, which pairs extremely well with Blake. Their dark, industrial, and immersive sounds set off the cosmic and uncanny qualities in Blake’s image; qualities that could be easily dampened by a lighter, folksier, Romantic or pastoral approach. I hope that this pairing with Lynch might inspire other multimedia interlocutors with Blake. I also hope that my engagement with the Sound Mountain archive in this videographic mashup will contribute to the work done by scholars like Liz Greene on Lynch’s sound and authorship. Finally, I offer this project as a contribution to the study of the history and aesthetics of visionary art, a subterranean river that continues to flow beneath the surface of cultural life and feed the roots of many artistic works.

- 1

See for example Martha P Nochimson: The Passion of David Lynch. Austin 1997; Justus, Nieland: David Lynch, Urbana-Champaign 2012.

- 2

See Howard Becker: Art Worlds, Berkeley 2008.

- 3

L. Caruana: The First Manifesto of Visionary Art, Paris 2010, 3.

- 4

Alex Grey: The Mission of Art, Boulder 1998, 25.

- 5

C.G. Jung: Modern Man in Search of a Soul, Boston 1933, 155-6, 158.

- 6

William Blake: Blake’s Poetry and Designs, New York 2008, 433-4.

- 7

Eric G Wilson: The Strange World of David Lynch, New York 2007, 24.

- 8

Wilson: The Strange World of David Lynch, 35.

- 9

Claire Henry: Eraserhead, London 2023, 66. See also David Lynch: Catching the Big Fish, New York 2006, 33.

- 10

See The National Gallery, Soundscapes/Past Exhibition, 2015, https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/exhibitions/past/soundscapes, 12.6.2024

- 11

Michel Chion: David Lynch, London 1995, 38.

- 12

Chion: David Lynch, 44-5. See also Leah Toth: Beautiful, If You See it the Right Way: David Lynch and Eraserhead’s Aural Tableau of Industrial America, in: Resonance, Vol. 2, No. 1, 56.

- 13

Sound Mountain Collection, https://www.prosoundeffects.com/collections/sound-mountain, 12.6.2024. On Splet see Liz Greene: The Labour of Breath: performing and designing breath in cinema, in: Music, Sound, and the Moving Image, Vol. 10, No. 2, 2016, 109-110; Liz Greene: From Noise, in: Liz Greene and Danijela Kulezic-Wilson (eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Sound Design and Music in Screen Media, London 2016; Liz Greene: The Unbearable Lightness of Being: Alan Splet and the Dual Role of Editing Sound and Music, in: Music and the Moving Image, Vol. 4, No. 3, Fall 2011, 1-13.

- 14

Raine suggests that Blake encountered Porphyry’s treatise «On the Cave of the Nymphs» in the version translated and published by Thomas Taylor in 1788, see Kathleen Raine: Blake and Tradition, Princeton 1968, 67, 75.

- 15

Kathleen Raine: The Sea of Time and Space, in: Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 20, No. 3/4, July-December, 1957, 319.

- 16

Raine: The Sea of Time and Space, 323.

- 17

Ibid., 318.

- 18

Homer, trans. Emily Wilson. The Odyssey. New York 2020, 63.

- 19

Raine, The Sea of Time and Space, 319.

- 20

S. Foster Damon: A Blake Dictionary, Hanover 1988, 458. See also Raine: «The Sea of Time and Space,» 320.

- 21

Raine, The Sea of Time and Space, 320.

- 22

Ibid., 322, 333-4.

- 23

The Fats Waller recording of «I’m Coming Virginia» (1927), is the only item on the soundtrack to not be sourced from the Sound Mountain archive.

- 24

Godwin, K. George: Eraserhead, in: Film Quarterly, Vol. 39, No. 1, Autumn 1985, 41.

- 25

Wilson: The Odyssey. 150.

- 26

Raine, The Sea of Time and Space, 324.

- 27

Ibid., 326.

- 28

Ibid., 327.

- 29

Ibid.

- 30

Ibid., 332.

- 31

Ibid., 321.

- 32

Ibid., 326. See also Kathleen Raine: Blake and the New Age, London 1979, 53.

- 33

Raine, The Sea of Time and Space, 325.

- 34

Ibid., 322.

- 35

Ibid., 320.

- 36

Ibid., 333-4.

- 37

William Blake: Blake’s Poetry and Designs, New York 2008, 433-4.

- 38

Raine, The Sea of Time and Space, 333-4.

- 39

Ibid.

Bildquellen

Abb. x (Teaserbild): Still aus David Lynch Presents William Blake’s “The Sea of Time and Space” (2025), Jacob Smith

Abb. 1-19: Gemälde «The Sea of Time», William Blake (1821), entnommen aus dem William Blake Archiv, zugeschnitten durch den Autor.

Bevorzugte Zitationsweise

Die Open-Access-Veröffentlichung erfolgt unter der Creative Commons-Lizenz CC BY-SA 4.0 DE.