The Tools of Research-Creation

Acknowledgement: Christoph Brosius has substantially contributed to this post by way of a short interview that we conducted with him on 30 May 2022. Brosius is a games producer, scrum master, consultant and teacher in the MA Digital Narratives.

In the opening blog post to the special series Researching, Teaching, and Learning with Digital Tools, Josephine Diecke, Nicole Braida, and Isadora Campregher Paiva have invited readers to explore the wide-ranging applications of digital methods and tools in film and media studies. Based on the areas of teaching and (self-)study, research, (interactive) websites as well as project management and project communication, specific use cases with their advantages and limitations will be presented and critically examined in the course of the series. The aim is to provide an open platform for discussing the various approaches and perspectives in order to focus on the dimensions of and workflows with digital tools.

The special series Researching, Teaching, and Learning with Digital Tools continues with a contribution by media practitioners and scholars Frédéric Dubois and Lena Thiele, who share their experiences with research-creation in the film school context. The two professors first chart out their approach, the types of tools that they employ in the context of the Master’s program Digital Narratives, and why the most promising digital tools for creative media practice are those that seriously invest in community and interoperability.

Introduction

Lena Thiele and Frédéric Dubois share a professorship in the Master’s program Digital Narratives at the ifs -Internationale Filmschule Köln. While Lena is responsible for «art and design»1, Frédéric tackles «media theory»2. The MA program is essentially designed so as to equip students in how to creatively craft digital stories, while at the same time critically reflecting on the technology used, as well as the societal relevance of their story, all based on a research-creation approach. Now in its seventh year, the young program mostly attracts storytellers interested in using mixed reality, web technologies and a combination of low- and high-tech applications to create a new language to tell their stories and to engage audiences. While working in practice, students at the same time encounter academic research. In this blog post, we revisit the main coordination, creative and communication tools employed in our MA program and illustrate the research-creation approach that we privilege, as well as the limitations resulting thereof. We explain coordination tool Spaces and creative tool Miro, and list our main learnings. We focus on the need to establish a set of criteria for deciding on the use of tools, while at the same time keeping the door open to new influences coming in from students and teaching staff. Especially in a fast-paced technological space like that of digital storytelling, educators need to remain flexible in tool adoption, while sticking to their curriculums’ exigences.

Research-creation

The approach to knowledge generation in the MA Digital Narratives is one of research-creation. This approach includes artistic enquiry methods, but more so, it places a creative project and/or process at the core of research. It means, in other words, that students start by defining a research question. From there, they go through a process that is characterized by iterative loops involving creative practice on the one hand and classic research on the other. The result is that students start—beyond the acquisition of narrative and production skills—developing an enquiry reflex and critical thinking. In the best of cases, this further leads to students being able to contribute both to the community of practice (e.g. VR storytellers) and to an academic community (e.g. researchers discussing immersion in storytelling), as one can see in our paper “Learning by Doing”. Before focusing on specific methods and tools, let’s get an overview of all tools used in our teaching, research and communications.

Tools for research-creation

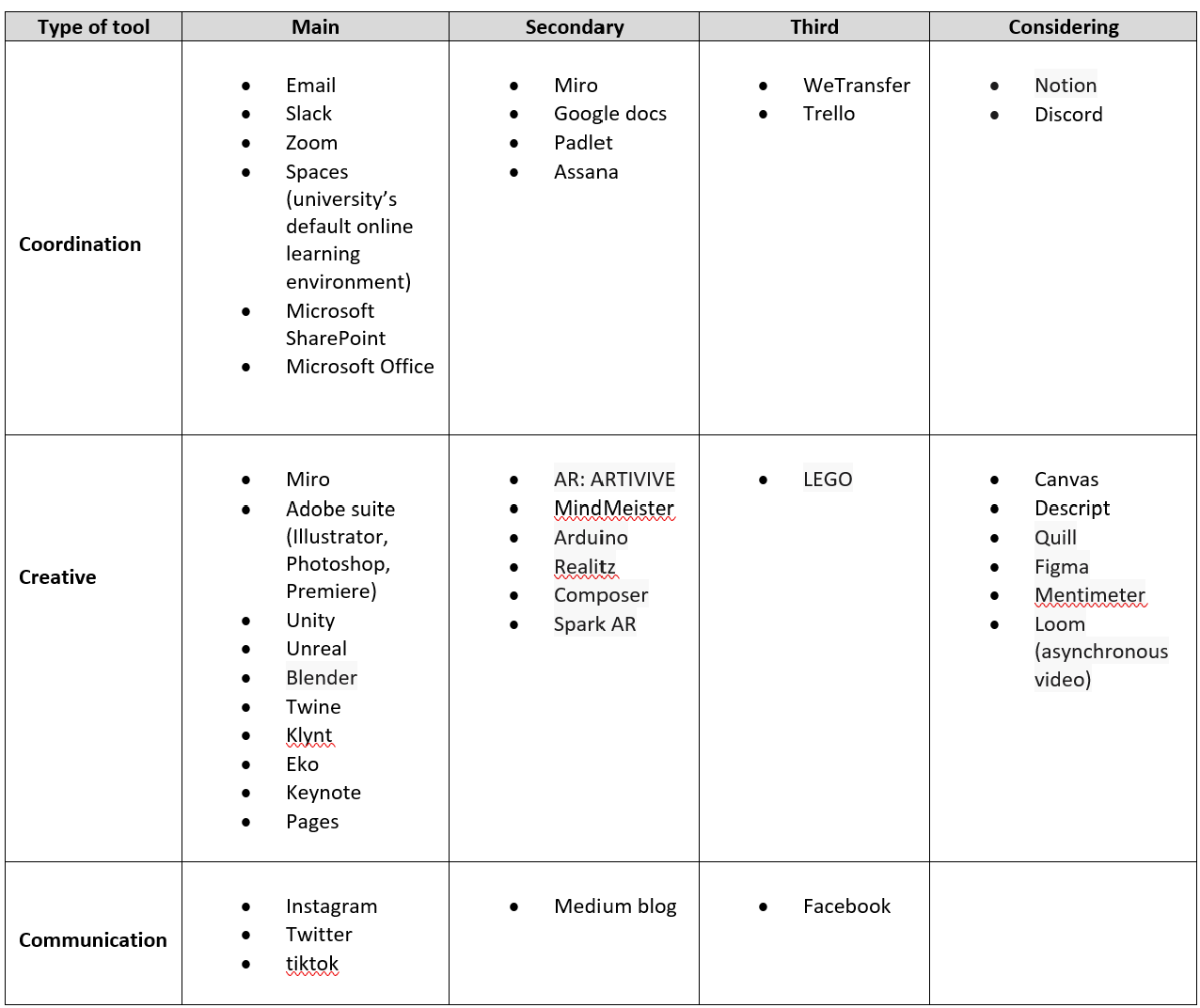

In our practice, we differentiate between three types of tools: 1) project management tools (referred to throughout as coordination tools), 2) creative media practice tools (or creative tools) and 3) communication tools, oriented towards outreach and public relations We will only discuss the first two types of tools, as the third type is common to many similar programs. In our understanding, what is important when settling on tools, is to develop one’s own stance. It could be a common department’s position, that of a school (if not too big), or it can just be that of a group of professors. In our MA program, we consider the following characteristics as key:

- Data mobility

- Data storage

- Data safety

- Active developer community backing the tool

- Active community of practice using the tool

- Possibility for co-creation

- Usable for rapid prototyping3

These characteristics were established over the years of the MA, where tools were tested and continue to be adopted, tested and reviewed in every given academic year. Tools come and go as they always depend upon teacher- and student-driven processes and methods.4

Table 1: Main tools in the MA Digital Narratives. Source: by the authors.

Coordination tools

The first type, coordination tools, are a regular installment in the educational setting. There is a main formal communication channel, in our case email communication, complemented by a more agile and informal tool, here Slack. Slack allows quick communication, exchange of ideas, inspirational sources or spontaneous sharing, when organized in clear channels and communication rules. The video conferencing tool Zoom is used for lectures, discussions and workshops. In our observation, most of these tools are standard and do not need an introduction. The notable exception is a tool we use to kick off teaching. As the university’s default online learning environment, Spaces is a portal through which professors share readers, address scheduling issues and provide workshops. It replaces what previously was called the Intranet. Spaces, like the Köln International School of Design website defines it, «is a Social Learning Environment (SLE) which has been developed by KISD – Köln International School of Design (Faculty of Cultural Studies, TH Köln, University of Applied Sciences) since 2008». The open source and WordPress-based solution «offers a communication platform, facilitates the organization of learning, and allows students to work together in a digital learning network. Students and teachers present their project, seminar or research work, share their research results, discuss online, and mutually support each other» (Ebd.). Spaces is a typical coordination tool focused on the teaching aspect. It permits data mobility in the sense that it accommodates all types of files. It facilitates the storage of data, has an active albeit small developer community backing it, and reaches out to a potential user base of 27,000 students. Last but not least, it enables co-creation via its interactive functionalities. It can be used for rapid prototyping, although the latter characteristic rather applies to creative tools. It is in constant development integrating cross-faculty feedback loops to optimize the features and interfaces.

Creative tools

Also used as a coordination tool, Miro is a canvas onto which content is posted by its users. Miro is a virtual whiteboard where participants can collaboratively work. To the contrary of Spaces, Miro is mainly used as a creative tool, due to its impressive number of features and the very intuitive user experience. Miro for instance counts a video-conferencing software, a mind mapping function and many other features meant to serve the different purposes of a multiplicity of users. Miro boards, which integrate elements such as multimedia files and plain text, are generally connected with each other. One of the limitations of Miro as a coordination tool, though, is its difficult relationship to numbers, to the quantitative, as our colleague Christoph Brosius notes5. Bridging data sets and setting up clever interactive connections among databases (e.g. relating calendar functions to guest databases) remains a weakness of Miro, he insists (Ebd.). It could be said that Miro invests in visual possibilities over data-driven potentials. When students engage in project conception and development, they most often need a space where to put all research scraps, mood and sound boards, and other planning documents. Canvas-type software such as Miro, are particularly well-suited for visual work in a team. One of the advantages of Miro is the scope of functions offered to users, who get to manipulate different source files via drag and drop. This, combined with the multi-user function—which enables different end-users to work on a same board at the same time—makes Miro a powerful creative tool. Initially, Miro offered limited data mobility. One could import information in different formats, but not all kinds, e.g. no vector graphics. This broke the user flow / ease of use. These days are gone. «From my observation, business models of services such as Miro always go in direction of data mobility. This is how portals hold on to users and end up winning», says media production educator Christoph Brosius. Regarding the other characteristics, including rapid prototyping possibilities, Miro has them all. This said, some functions continue to be glitchy, including collaborative work on Google docs within Miro, or the fact, on a more political level, that it does not play by open-source standards. The team behind the MA Digital Narratives has picked up Miro for its functionalities, without necessarily going through a full competitive analysis on aspects such as data protection or ease-of-use. There are many other whiteboard services, including the Stuttgart-based Conceptboard, which among other claims to be strong on data protection. When settling on the tool, we have simply verified whether Miro is in compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), without pursuing the data safety issue beyond that. Even though Miro’s pricing is higher than that of other whiteboards, it remains accessible for our MA program. Regarding student feedback, Miro is highly regarded by our visual-oriented students, who appreciate collaborating on a whiteboard. Beyond Miro and competitor whiteboards, there are more specific tools when it comes to creating web-based or immersive narratives.

Branching and web-based narratives

For most of our creative developments, we aim to allow for rapid prototyping and testing in the iterative process of ideation6. For branching and web-based narratives we currently use Twine and Klynt. We set out to develop stories in Twine, applying the knowledge of dramatic structures, environmental narrative, character drama, and iterative development approaches. Twine is an open-source tool for telling interactive, nonlinear stories. It does not require any code to create a simple story, but the stories can be extended with variables, conditional logic, images, CSS, and JavaScript at the end of the development. Students can completely focus on the creative development of their dramaturgy, it can easily be tested in a prototype stage and even implemented in a full project. In that sense, Twine matches the characteristics that are dear to us in most regards when it comes to tool selection.

Immersive narratives

When creating narrative forms meant for virtual reality or 3D environments, we train students on how to work with Unity and Unreal.As there is already a lively discussion on the merits and disadvantages of one over the other, especially in the video game scene and the film sector, suffice to say that we have found our characteristics best served in Unity when it comes to rapid prototyping, and by Unreal when one considers data mobility. We have decided not to settle and rather consider both tools depending on the teaching goals and further development of the products and the market. This decision to have both in our repertoire simply means that we need to keep working with outside specialists on both technologies and ensuring that students get adequate support. From our vantage point it is quite hard to say whether one or the other is more advantageous when it comes to interoperability. We know that both Unity and Unreal game engines are increasingly integrated with other tools via interoperability standards, but as Tim Marler argues on the Tech + Narrative Lab, this does not guarantee practical interoperability. We are still to test interoperability for both engines with our next MA cohort.

Learnings

When defining the stance and the characteristics that orient the choice of tools in media and communications scholarship, we plead for considerable research, definition of clear criteria and structure and a constant evaluation process. There is value in testing and practicing for coming together on common characteristics. For example, in our experience it is okay to be in favor of open-source technologies and to push in favor of using those in a priority fashion. But in practice, it is sometimes not possible to only rely on open-source technology, especially when trying to push the boundaries of storytelling and continue being innovative. When it comes to settling on specific tools, especially creative ones, we are in constant communication with our creative needs, the changes in the market, taking into account the regulations of the school when it comes to the legal aspects (e.g. data protection). When it comes to coordination tools, we try to stick with tools privileged by our film school, as exemplified by Spaces, so that keep a common language with our fellow colleagues. In any of the decisions, we keep our ears in tune with what practitioners in digital storytelling, often early adopters, pursue. It does not mean that hop on any trend, but we are in continuous testing of new tools through the input of our practice-driven teaching staff and students. We do not exchange much with other higher education institutions for the choice of tools, but this exercise in open scholarship for this blog and this specific series is a first foray in attempting to reach out and listen to peers. The most important is that at some point, characteristics are agreed upon and lived by, so as to facilitate the quick choice and testing of tools, evaluating the pro and cons to stay in the learning process. While we have full license to take decisions on tools at the department level, we also consult with the film school colleagues and seek inspiration on what tools they use. We create a proposition of tools we aim to use on the department level. This is then checked by the institution’s technical department on legal and licensing possibilities. The luxury that we have at the university level is that we can offer a safe space for experimenting outside the many constrains of media production. Students also have the advantage of not being bogged down by archiving and data storage considerations as much as professionals with an established practice needing to choose tools that will be able to migrate their existing data over. The data storage characteristic is thus less stringent in school, which is an opportunity for experimenting with various tools, especially at a time where one explores media and communications processes and methods. This said, we do address data storage with our students in the context of the MA curriculum7, as archiving, compatibility and other data management issues are considerations to be accounted for in professional life. In what might sound like a steep thesis, MA lecturer Christoph Brosius says: «Miro and Mentimeter are the knife and fork of teaching»8. These tools of teaching don’t always correspond to all the characteristics that are dear to us. They generally only address this or that characteristic. Yet, one of our learnings, over the years, is that regarding teaching, educators need to be flexible. Teachers need to adapt to tools that are important in the professional and creative sector, or to the academic one. In an MA program like ours, where the ambition is one of research-creation, tools are often dictated by a willingness to serve creation and research first and foremost. Classic teaching and didactical tools like some branded as Open Educational Resources (OER) might be less appealing to students and educators. Although teaching is necessarily a building block for any MA program, research-creation programs might have their antennas oriented towards state-of-the-art tech, rather than edtech. This is due to the fact that our teaching is much in line with a learning by doing paradigm. Reflecting upon the choice of tools in combination with our research-creation approach, makes us realize that most new tools that we test, are tested directly with students and teachers, most often even brought-in by them. This is a routine that we are used to. The question remains whether research-creation orients us all to choose certain tools over others or if it is the other way round, where the tools being used influence the type and quality of research-creation that we are generating. We would tend to argue that it is a mix of both, with industry tools still having the upper hand, i.e. we are not in control of new tools hitting the industry and thus the agenda-setting by popular tools does happen. But at the same time, having a set of criteria, including on data mobility requires us to keep looking for tools that are data-friendly and that allow for practical research. In certain instances, and thanks to our interdisciplinary group of students (some of which come from computer science, or sound studies), projects might develop out of low-tech tools or an unusual combinational of tools. This is the creative space that students have and which continues to show us every year that research-creation allows for creative and research surprises thanks to tools that students and teachers empower themselves with.

Conclusion

Rapid prototyping, easy access, quick results to test, possibility for co-creation and many of the other characteristics that we have settled on for best fitting the research-creation approach are only an illustration of what scholarly teams can agree on. Finding common ground on those makes one’s life in media and communications scholarship easier. This is especially so when research and creation both need to be advanced in parallel, and put in dialogue. This said, it is important to differentiate among the types of tools, be they coordination, creative and communication, so as to facilitate a fruitful exchange over the tools of research-creation.

- 1For more on Thiele’s journey, read her chapter : Thiele, L. (2021). Navigating the industry as an independent creative. In Interactive Storytelling for the Screen (pp. 48-56). Routledge.

- 2For more on Dubois’ journey, read his PhD thesis: Dubois, Frédéric. 2021. Interactive Documentary Production and Societal Impact: The Case of Field Trip. Doctoral dissertation, Filmuniversität Babelsberg Konrad Wolf.

- 3Rapid prototyping is a method stemming from computer engineering enabling quick development of complex media/tech environments. This allows the creative team to see how a storyworld can for instance look and feel like before going into full production. Ian Gibson provides a workeable definition of rapid prototyping in product development, see Gibson, Ian. "Rapid prototyping: A review." In Virtual Modelling and Rapid Manufacturing: Advanced Research in Virtual and Rapid Prototyping Proc. 2nd Int. Conf. on Advanced Research in Virtual and Rapid Prototyping, 28 Sep-1 Oct 2005, Leiria, Portugal, p. 7. CRC Press, 2005.

- 4The tools in table 1 are currently in use, but because of the mediainnovation environment of this MA program and the fact that processes and methods keep adapting, this bird’s eye view can be described as volatile. For an in-depth exploration of media innovation, read: Dubois, Frédéric. 2020. “Media innovation and social impact: the case of living documentaries”. The Journal of Media Innovations, 6 (1), 23-37.

- 5Christoph Brosius (personal communication, May 30, 2022).

- 6Thiele, L. (2016), Iterative Produktionsprozesse. In Story Now: Ein Handbuch für digitales Erzählen (pp 67-71); mixtvision Verlag; transmedia bayern.

- 7The MA has a module called Project. In Project 2 and Project 3, we address most data management questions.

- 8The MA has a module called Project. In Project 2 and Project 3, we address most data management questions.

Bevorzugte Zitationsweise

Die Open-Access-Veröffentlichung erfolgt unter der Creative Commons-Lizenz CC BY-SA 4.0 DE.