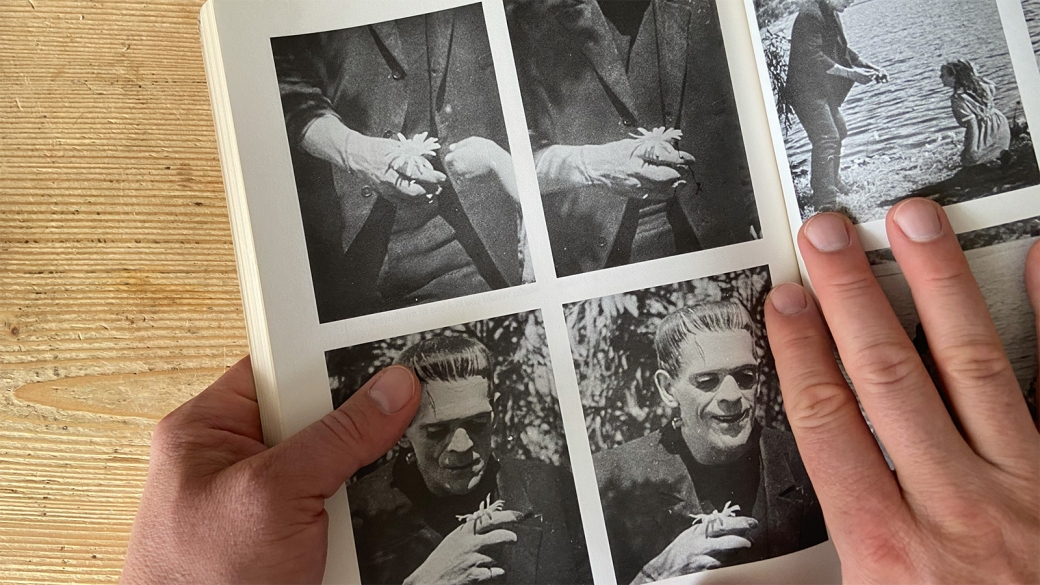

Still aus Practices of Viewing (2021), Johannes Binotto

A Manifesto for Videographic Vulnerability

- There is no best practice.

(No one asks a painter «Which is your best brush?» Knowing how to edit in AdobePremiere is not any better for making video essays than using iMovie or drawing on a piece of paper.) - We use the tools at hand and use them in unplanned ways.

- Videographic practice is an affective, multi-sensory, and bodily experience. We use our bodies, our memories, our intuitions, our flaws.

- What does «essay» literally mean? («essayer»: to try, to try out, to test... [and to fail])

- Restrictions are productive, they are arbitrary but never random (and meant to be overstepped).

- None of us know more than the others in the room, but we all know different things.

- Completeness is not the goal and intactness is not the start – we aim for multiplicity and inexhaustibility.

- Let's not make video essays in order to master anything.

- Seek process, not outcome!

- Let’s not only use audiovisual sources to analyze, question, and problematize the material itself, but let’s also use (misuse? abuse? re-use? appropriate?) them to think about/through/with our lives, cultures, societies at large.

- Let's stop talking about success and start talking about resonance.

- Embrace mistakes, accidents, glitches, and chance!

- Perfection is a disease.

- Be vulnerable and use your privileges accordingly.

The manifesto came out of our own desires and anxieties, and out of multiple conversations we had with each other and our colleagues over the past few months. We noticed how central the term ‹vulnerability› became when we tried to assess the new directions in which video essay culture seems to develop. This includes an increasing trend towards ‹personal› inscriptions, modes, and narratives. The manifesto is an invitation to think through and build on our individual and collective vulnerabilities in videographic thought and practice. The following conversation adds further context and discussion to the points laid out above.

Evelyn:

I think it’s impossible to talk about vulnerability without talking about the personal – personal investments, motivations, stakes, experiences, identities, bodies, etc. Given how video essays increasingly seem to implicitly and explicitly involve personal modes and the makers’ personal positions, I’m wondering whether we can speak of a ‹personal turn› in videographic culture.

Johannes:

Certainly, but then the personal and the vulnerability that goes with it was always present. Maybe it was not highlighted though. Or it was something that we as scholars were trained to pretend to not employ. Instead we learned to speak from a position of expertise and established knowledge, one that is more guarded against possible attacks. Speaking for myself, I feel that with video essays I’m doing something for which I wasn’t prepared and thus more exposed to criticism. My video essays forced me to rely on my own resources. So, it became inevitably personal. In reaction to this I increasingly have this urge to appear in my videos and thus in the films that I am working with. To be physically present in them, as a vulnerable body. And one of the explanations for me is that I’ve always already had that desire, also when quoting something – to be in conversation, to be in the same room with the author I am quoting.

Evelyn:

Right. Perhaps it’s better then to speak of a ‹personal (re-)turn›? And, of course, many of the most canonical essayistic texts build on the personal mode extensively. For example, Walter Benjamin and, above all, Roland Barthes frequently evoked the personal in their analyses of images, texts, and art. I had never really thought about citations in the way you do, though. Obviously, citations in academic writing fulfill a function, too – they legitimize your own arguments and voice. And with videographic methods, I am increasingly ‹functionalizing› the audiovisual sources more and more as well. I used to be very hesitant about admitting this in the past, but I have definitely made videos in which I was less interested in deeply analyzing the films themselves per se, but more so in using them as material – as images and sounds through which I could express something that I wanted to express anyway. So, just like you might try to inscribe yourself into your material, I guess, I’m inscribing my material into my voice?

Johannes:

I think there exists a mixture of these two positions. Thinking of it psychoanalytically, there’s this idea that my own desire is actually something that is out there in the texts that are not mine. What I find interesting is neither attempting an objective pure analysis of the object, nor just obsessing over my own desire, but rather experiencing my desire being awakened when I read something or when I watch something. And so often I have a particular author pop up somewhere in my text, not because it is really necessary for the argument but just because I want that person to be present.

Evelyn:

Yes, I feel that way, too. And when I say that I approach some projects knowing that I want to express something before even really digging into the audiovisual sources, then as soon as I start working with the material, it reveals new insights to me and it influences and changes the initial expressive idea anyway. There’s a resonance that comes out of these interactions between me, the material I’m working with, the associations they might evoke in others, the associations their makers built on, etc. Hartmut Rosa uses this notion of ‹resonance› as a counterbalance to the overstimulation and intensified speed of daily life in the 21st century, and I sense that it gets at one of the key attractions of videographic experimentation, too.

Johannes:

I totally agree. However, it’s all easy to make a call for being more experimental, more personal, vulnerable, and for exposing yourself. Because, in the end, it is also a question of privilege. Can you afford doing that? What are the risks? I’m really glad that I started to make video essays rather late. It allowed me to explore something as if I was a child. To play around with it. But I’m aware that I could do that only from a position of security. I can afford to show myself vulnerable because I’m under no existential threat.

Evelyn:

That’s a very important point. Speaking as someone in a more junior position than you, it’s something I’ve thought about a lot. Some people warned me that it might be too risky to start an academic career as a video essay scholar/maker because it is not as fully established yet as other fields and methods might be. At the same time, I often think that being in academia as a junior scholar is precarious no matter what, so I might as well go after what interests me most, even if from a more precarious position.

Johannes:

Yes, absolutely. The problematics of academia and the job market almost force you to be experimental and to try something new. Because this promise of playing it safe has proven to be false anyway. I think it’s helpful to think about this work through/as resonance, as you suggested. Resonance also presupposes that there is a body – something with which to resonate. This already works against this idea of pure thought, right? This outdated but still existing ideal of pure disembodied thought would not have resonance – it needs another body that it sets in motion, that it reverberates with. Again, I’m thinking of psychoanalysis here and what Jacques Lacan said about the voice: the voice needs the other as a vessel in which it can resonate. He would say the voice does not exist without the hollow cochlea of the ear. We would not hear anything in a vacuum without any walls to hit sound back from. Thus communication presupposes bodily presence.

Evelyn:

True. And that’s highly relevant to the bodily inscription you addressed earlier, which, to me, has so much to do with how I use my voice in video essays, too. I use quite a lot of voice-over narration – partly because I’ve always liked acting and it’s a way to indulge in that joy, but also because it’s a way to claim the video as my own (given that the images I’m using are already ‹not quite my own›). Recording voice-overs is a really interesting, very intimate and very resonant activity. You sit in a sound booth or under a blanket you’re using to drown out noise and you’re listening to your own voice with a certain attentiveness that you rarely use otherwise. Same with the sound editing. But even when I use text on screen, I always write, read, and edit it as if I’m hearing the words out loud – I pay attention to rhythm, breath, tone, etc. In this, writing for video essays feels quite different from writing for a written publication, do you agree?

Johannes:

Certainly. You mentioned Roland Barthes, who is probably stylistically my most important role model. I always wanted to emulate his sound. I very much think about the sound of a certain text, probably even more than about its content. But then we try to find our own sound. I’ve seen video essays that made me speechless: how did their makers achieve to see so many films? But then I realize: well, if it has already been done, I don’t need to do it. Same with writing. I was always very impressed by these texts that give these grand overviews. I cannot do such a thing but then maybe I’m also not really interested in doing that. Rather, it allows me to make my own weird, new experiments. But these experiments in turn are influenced by all the authors and makers I have been exposed to. Students sometimes tell me that they just want to trust their gut instead of relying on some theoretical position. They want to be free of external influences. But I always tell them: there’s no such thing, you are influenced, inevitably. And if you want to trust your gut, you have to think about what you’ve eaten. If the only thing you’ve eaten all your life is pizza, your gut will only direct you to something like pizza.

Evelyn:

That’s also true of the material we use, of course. The texts and images and sounds that we reuse are influenced by the things that their makers had digested before and they are always products of multiple voices in that way. Sometimes I wonder if, with all the liberties that come with the personal mode and with our vulnerability, there’s a temptation for us to lie to ourselves, though. To what extent is our courage to be vulnerable perhaps also an escape from academic accountability? Compared to posting or publishing academic texts, I certainly feel way less inhibited to post a short video on my Vimeo channel, especially if it’s in a more poetic or personal tone.

Johannes:

I think it would help if we let go of this idea of completeness or ‹purity›. That anything I share or publish could ever reach this level of purity and instead embrace the half-said, the unsettled, and accidental. Not trying to say everything that could be said about a certain subject because claiming to have said everything would be a lie anyway. For me, the most poignant example for this is still Alain Resnais’ Nuit et brouillard. One of the first films about the Holocaust and yet only 30 minutes long. I think just the length is already such a powerful statement. It tells me from the start: this cannot be all. And it never pretends to be all. It makes clear to us that it is impossible to ever make an exhaustive film about the Holocaust. All can never be said. And already the filmic form itself shows this necessary incompleteness.

Evelyn:

It’s important to mention, too, that this ‹purity› doesn’t exist in our personal inscriptions, either. Even if/when we make ourselves vulnerable, we open ourselves up personally, we are still using performance and embody personas. However, do you also feel like we’re allowing for a certain inexhaustiveness, openness, and vulnerability more in the videos themselves and less in the accompanying written statements with which they’re commonly published? Or perhaps we’re even undoing some of the vulnerability of the videos with the written statements? I’ve certainly written such texts with the assumed expectation that I had to include all the academic references that I didn’t get to or didn’t want to include in the video. There is, of course, a pragmatic benefit to doing that in terms of academic merit. Publishing videographic pieces might already be somewhat risky and they’re not as quotable as traditional publications are, so it makes sense to write the accompanying statements in a way that makes up for that. But perhaps this also counteracts some of the openness and also the legibility of our videos (the elements that make them accessible to more diverse audiences). It certainly feels odd sometimes to make a video that is very experimental and poetic in tone and then pair it with a fairly conservative, jargon-heavy academic statement.

Johannes:

I am not sure if I would put poetic tone against academic quotation. Often I would include a quotation not necessarily to make things more explanatory but rather to open up the video with allusions to other discourses that perhaps only a handful of people or maybe even only me would pick up on. And I am doing that hopefully not out of a form of self-indulgence but as a gesture towards multiplicity. A gesture that I am not in complete control of how and what is seen, understood or misunderstood in my videos. Here we come to a really interesting paradox: as scholars in the humanities we would all grant an inexhaustiveness to what we call primary texts. You’d look stupid if you’d claim: Here is the final reading of Shakespeare. But when it comes to our own stuff we are far more inclined to hold on to a fantasy of control and completeness: This is what I meant and I want you to understand only that. I remember, I once showed a probably rather obscure video essay to a diverse audience and afterwards I talked about some of the more hidden questions that the video is connected to for me. And then someone asked: «This is interesting what you say, but why didn’t you put it in the video in the way you are now talking about it?» And I immediately realized, because I am happy with my video and my talk not being the same and that some would not see certain things I wanted to address in the video. Which in turn also means that hopefully they can see something addressed in my video that I did not really think about. So I try to think of video essays more like an offer and less like an enforcement. You offer something and people can take from it what they find useful. And it can be that some found the talk afterwards much more interesting than the actual video. There are also critical texts that I prefer to the actual films they are discussing.

Evelyn:

That very much resonates with my idea of video essays as archives in- and of themselves. When you work with pre-existing sources, you’re drawing on various archives in a general conceptual sense. But you’re also creating and curating new archives, new layers of material, ideas, and associations – whether they be personal, collective, cultural, or educational. I always think of any video I make, especially when it’s based on more than one source, as both the concrete video that I publish, but also as this second, imagined, less visible entity – this bigger archive of all the sources and contexts from which the fragments I use stem and all the relationships that these sources might evoke with each other, with other sources and with further influences. In a way, we’re doing the same with our written texts, aren’t we? Creating archives of references and resonances. We just exert our control over the way our work might be experienced differently in this form. When we share a video online, we don’t know the context in which someone will watch it or the device they will use to screen it, or their attentiveness. But by adding music, for example, and by creating a rhythm, we take a certain amount of control over the viewing/listening experience that we don’t have in written form quite as much. However, in writing, we might do much more framing, explaining, contextualizing that guides our readers more explicitly – again a different kind of control.

Johannes:

But then, paradoxically, I find a written text to be much more interactive than a video. In some ways, a video is more controlling than a text because the form is so forceful and so linear. In a text however, I would jump around, change speed, skip, skim, and browse much more freely. And maybe that’s why I have certain reservations against too explanatory, too authoritative video essays because I feel that since they already are so linear simply due to the video medium, I wish all the more for freedom on their argumentative level.

Evelyn:

It’s ironic to think about the video essay as being restrictive in this way because the ability to pause, to go back, to go against chronology and linearity, etc. is so central to what the video essay can do with its sources. In the Laura Mulvey sense, digital technologies allow us to watch films differently and against their linear, original or assumed spectatorial experience. But then I consciously or subconsciously work on the pacing, rhythm, and development in my videos, as if everyone who watched them watched them in their entirety, in a concentrated manner, on a single screen, etc. I certainly enjoy sharing my videos in a festival or conference setting in front of a live audience much more than online. In part, because this way I feel more in control over how they’re going to watch my work.

Johannes:

Talking with you about this dialectic of openness and control now also makes me understand better why we are drawn to certain so-called major films. Not because they are better but precisely because due to their status as masterpieces they impose so much control, so that inserting more openness into them is a much more radical act.

Evelyn:

Yes, that’s really key to me as well. That way we go beyond the more cinephilic understandings of videographic work. For example, you and I have both made video essays about Hitchcock films – one of the grand figures of cinephilic discourse. I think, there’s an easy assumption that working with such well-known, ‹overstudied› material will either fall into the cinephilic category or it will deconstruct the material – make visible or audible the problematics, questionable politics, etc. of the material and/or its makers. But neither of those are my key ambition and I would argue that both of us have done something different with Hitchcock. By reflecting on the personal viewing/listening experiences that we and others have had with such canonical films, we can poke at a certain cultural unconscious that takes up a lot of space in this imaginary mosaic of cultural associations and shared influences. By making a video essay, we can not only make ourselves vulnerable, but also break down our materials into vulnerable fragments and expose their vulnerability.

Bildquellen

Abb. Still aus Practices of Viewing (2021), Johannes Binotto

Bevorzugte Zitationsweise

Die Open-Access-Veröffentlichung erfolgt unter der Creative Commons-Lizenz CC BY-SA 4.0 DE.