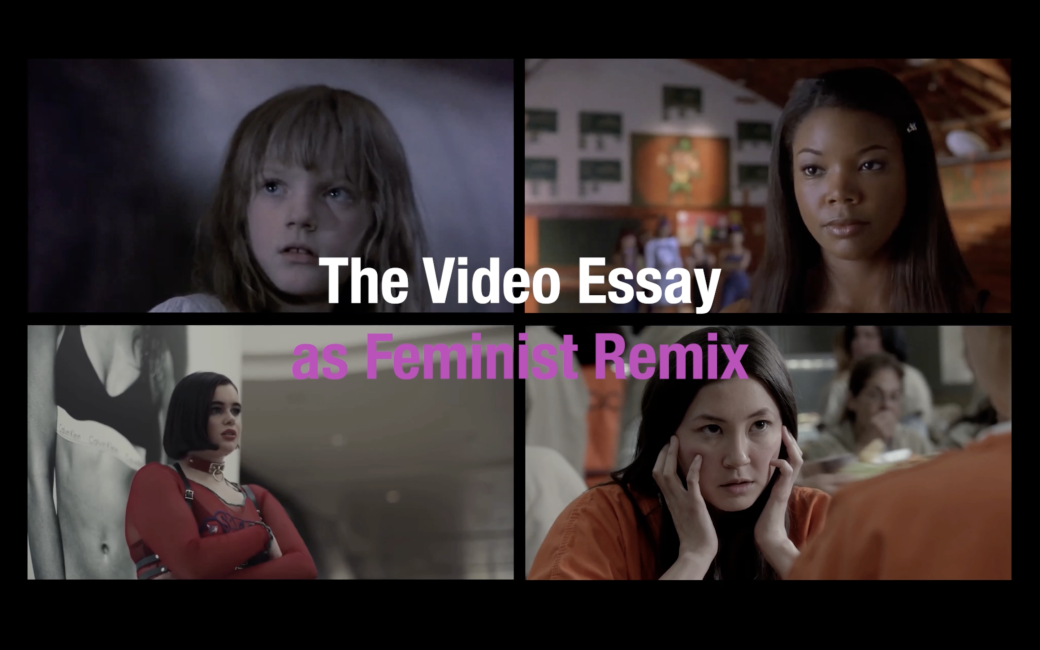

Still aus The Video Essay as Feminist Remix (2024), Kristina Brüning

The Video Essay as Feminist Remix

Centering Actors' Labor and Experiences

Building on feminist videographic work, this video essay considers the elusive relationship between on-screen representation and media production practices.

Revisiting video essays by Laura Mulvey,1 Allison de Fren,2 and others, Catherine Grant finds that these scholars not only comment on audiovisual content in their work, but they utilize video essays to ‹remix› their research objects to examine female agency, stereotypes, and looking relations.3 In this way, Grant argues, feminist videographic criticism can make visible what might not be perceived as easily otherwise and has a unique potential to not only display, but to actively disrupt the politics of representation.4

In line with Grant’s observations, I suggest that the tools of videographic criticism enable us to produce what I call a ‹feminist remix›,5 which interrogates how intersecting hegemonic ideas about gender, race, class, sexuality, etc. shape both what we see on screen and the production context and working conditions behind the scenes.6 Using feminist remixes as teaching tools or asking students to produce their own feminist remixes promises to enrich classroom discussion and to offer fresh perspectives on various types of screen media by bringing labor into the conversation.

Here, I use a feminist remix to spotlight the experiences of the actor as worker, centering female actors and their labor at the intersection of production and representation. Structured into three parts, this video essay blends scenes from films and TV series from the past 60+ years with actors’ discussions of their experiences on set and the challenges they faced, particularly in terms of negotiating their on-screen portrayals of young women.

Part one brings together unedited scenes from Some Like It Hot (Billy Wilder, 1959), Euphoria (HBO, 2019-), and One Tree Hill (The WB/The CW, 2003-2012) to emphasize the persistent confinement of women on screen to stereotypical, sexualized characterizations across time, mediums, and genres. Amy Lawrence calls this «the problem of the woman’s voice»: female characters are portrayed through a male, oftentimes sexist lens, which effects the silencing of women’s authentic voices on screen.7

Part two overlays edited versions of the same film scene and TV episodes with excerpts of actors’ interviews and podcasts. This feminist remix silences the words that were written for the women to say and instead reunites the actors with their off-screen voices. The imperfect match of audio and visual points to absences and questions that remain. Guiding viewers to see and experience the material differently, the actors’ recollections entice us to confront how gender norms and misogyny also affect labor behind the scenes.

Part three further centers female actors’ agency and experiences by convening an audiovisual roundtable. Despite the actors’ varied projects and intersectional identities, common themes emerge, pointing to the need to further interrogate actors’ role in media production.

- 1Laura Mulvey: Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (remix remixed 2013) in: Catherine Grant et al., [in]Transition: Editors’ Introduction, in: [in]Transition: Journal of Videographic Film and Moving Image Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 2014.

- 2Allison de Fren: Fembot in a Red Dress, in: [in]Transition: Journal of Videographic Film and Moving Image Studies, vol. 2, no. 4, 2016.

- 3Catherine Grant: Looking at To-Be-Looked-at-Ness: Feminist Videographic Criticism, in: [in]Transition: Journal of Videographic Film & Moving Image Studies, vol. 4, no. 1, 2017.

- 4Ibid.

- 5I keep my definition of ‹feminist remix› intentionally broad as I hope that – in the spirit of the discipline – other video essayists liberally use the term and further evolve what can be considered as a feminist remix. I also do not claim to be the first to produce a feminist remix, and this project has been inspired by many brilliant videographic works by more experienced scholars. See, for example, Catherine Russell and Shannon Lynn Harris: Barbara Stanwyck Rides Again, in: [in]Transition: Journal of Videographic Film & Moving Image Studies, vol. 8, no. 3, 2021.

- 6Although not always at the forefront of videographic work, there are some excellent videographic explorations of labor behind the scenes. See, for example, Katie Bird: Feeling and Thought as They Take Form: Early Steadicam, Labor, and Technology (1974-1985), in: [in]Transition Journal of Videographic Film & Moving Image Studies, vol. 7, no. 1, 2020. See also Aaron Taylor: Thinking Through Acting: Performative Indices and Philosophical Assertions, in: [in]Transition Journal of Videographic Film & Moving Image Studies, vol. 3, no. 4, 2016.

- 7Amy Lawrence: Echo and Narcissus: Women’s Voices in Classical Hollywood Cinema, Berkeley 1991.

Bildquellen

Abb. Still aus The Video Essay as Feminist Remix (2024), Kristina Brüning

Bevorzugte Zitationsweise

Die Open-Access-Veröffentlichung erfolgt unter der Creative Commons-Lizenz CC BY-SA 4.0 DE.