«Seeing Through Race» & Attempting to See through Media Studies

An Interview with W.J.T. Mitchell by Ömer Alkin

The abridged German version of this text was published in Zeitschrift für Medienwissenschaft, No. 26, 2022. Deutschsprachige Version dieses Beitrags (in gekürzter Form) hier.

In his 2012 book Seeing Through Race, W. J. T. Mitchell explores the relationship between medium and race.1 The written interview asks Mitchell about the comprehensive theoretical introductory chapter of his study and his suggestions for dealing with racism. At the same time, the conversation revolves around the transferability of Mitchell’s critical reflections on racism to the local system of science culture and the current relevance of his theses in the context of cancel culture, science culture, and media studies.

Ömer Alkin Dear Tom, I would like to begin by outlining the main ideas underlying this interview. Our conversation will be about your central argument from Seeing Through Race, about stereotypes as resistant images that cannot be destroyed and about «race» as a medium as well as «racism» as an unavailable, affectively highly charged reality. Due to the medium of the interview, however, it is also about your role as a discourse node of a media studies culture and its meta-medial moment: media studies as an academic culture cannot decouple itself from the affective and structural situation of «racism» – even if it is particularly capable of reflecting phenomena of racism.

Our journal issue is interested in positionalities and therefore in both of us as people in our sociocultural matrix. If you ask me, this also involves my meta-medial phantasmatic relation to you as a white intellectual, which we will only be able to talk about here to a limited extent, but which might be part of the dynamic of our conversation. The main goal of this conversation with you is to reflect on the medial situation of media studies and the cultural intertwining of visual and academic culture via your book and the theses and arguments you put forward there. For this purpose, I have to start with a question from the neighboring discipline of media studies: art history.

There has been a scholarly dichotomy between Bildwissenschaft and Visual Culture2 since about the mid-2000s – charged with interpretive struggles and discursive conflicts, which we can only discuss here marginally.3 Basically, in my opinion, the conflict – apart from theoretical assumptions – between Image Science (Bildwissenschaft) and Visual Culture is at the same time structured by the dichotomy «uncritical of institution» and «critical of institution». To put it completely simplistically: male-dominated science system (Bildwissenschaft) vs. feminist institution-criticism. In Germany, you are seen for the most part as a scholar of Bildwissenschaft. From my point of view, this is ironic, since you are also considered a central founder of the (in-)discipline of visual culture, which illustrates the complex situation between Image Science and Visual Culture (and art history is where this conflict started). Your last major theoretical work is called Image Science (2015). This is important to know, since it takes up the logic of the German term Bildwissenschaft for the English-speaking world.

Could you briefly describe your observations on these tensions between Image Science and Visual Culture?4 I am interested in whether this conflict or differentiation plays a role for you. I think this will help readers to better understand how you unfold your central arguments in Seeing Through Race and what this has to do with media studies and racism – our focus in this issue of Zeitschrift für Medienwissenschaft (ZfM).

W.J.T. Mitchell I have to admit that I am rather innocent about these divisions between art history, or Bildwissenschaft, on the one hand, and visual culture/media studies on the other. Perhaps this is because I came out of a third discipline – literary studies and cultural theory – that felt free to range over these borders. I have never felt particularly comfortable being hemmed in by labels, or pigeon-holed in a position of fixed identity. I have been a member of affiliate of four departments at the University of Chicago: English, Art History, Cinema Studies, and the Department of Visual Art, and spent forty years as editor of the interdisciplinary journal Critical Inquiry, a quarterly devoted to criticism and theory across the humanities and social sciences, including the history of science. When people ask what my academic specialty is, I answer that it is «iconology,» the study of images across the media. I see the foundations (but not the boundaries) of this discipline in Erwin Panofsky and Aby Warburg’s expansive view of art history. But I take it to extend beyond the sphere of the canonical visual arts into mass culture, advertising, comics, television, and everyday life. So visual anthropology, archaeology, and paleontology are, for my purposes, open borders that invite enrichment and expansion of the study of images. And my roots in literary study keep drawing me back to issues in the study of metaphor, narrative, and what Fred Jameson called «the poetics of social forms.» My deepest critical roots are to be found in the writings of Marx and Freud, leavened by the long history of liberal democratic theory re-framed by Foucault. The epistemological subsoil of my thinking is located in Darwin and my pre-literary obsession with mathematics, which was my major as an undergraduate. My love of pure mathematics has never gone away, and probably explains my penchant for abstraction, theory, and diagrammatic «conceptual topologies» as a dialectical counter-weight to particularity and historical specificity.

When it comes to racial identity, I have resisted the label of «white intellectual» in favor of something more specific. I am a descendant of an Irish father who died when I was five, and a German working-class mother who raised four children on a meagre salary in a small town in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountains. My best childhood friend was a Paiute Indian, and I learned my first lesson in racism when I heard him denigrated as a «redskin» by an older white boy. My adopted racial identity is Hibernian, in solidarity with the 300-year resistance of the Irish to the bloody, racist occupation of my imagined homeland by the English. As a footnote, the settler-colonial conquest of Ireland provided a model for Hitler’s plan for expanding the Third Reich into Poland.

Ö.A. On your website one can find the information that the title of your next book will be «Seeing through Madness: Insanity, Media, and Visual Culture» – and I think the preference to Visual Culture in the title shows that for your own positionality the dichotomy between Visual Culture Studies and Bildwissenschaft really does not seem to play a major role.

How do you personally deal with the tension of working in a scholarly field that is structured by dynamics of power which are rather hostile to people from working classes etc. especially if one considers your work’s critical heritage (Marx, Foucault and Freud)? How would you describe this relation between being critical about culture in your theoretical work and at the same time playing by the rules of academic systems that underlie exactly those dynamics you are arguing against?

W.J.T.M. There is no question that academic scholarship in American universities is built on a foundation of white privilege. This does not start at the university level, but is programmed from pre-school to kindergarten, all through the public school system. Race and class are deeply intertwined in American education. The long struggle of affirmative action, not only in education, but in employment, housing, childcare, and health services, has had very uneven success in combatting structural racism. And worse, a pseudo-egalitarian rhetoric of «equal opportunity» and race-neutral democracy has the effect of erasing the consciousness of white privilege. A friend of mine describes it as riding a bicycle with the wind behind one’s back. You don’t even notice it, and feel that it must be a result of your own superior prowess as a cyclist.

I see the current wave of «woke» and «cancel» culture as a historic moment of reckoning with this reality, which at the same time has provoked an intense reaction of denial and refusal of acknowledgment. Thus «Critical Race Theory» in the U.S. has been demonized as pernicious propaganda by the right wing, and turned into a political wedge issue. It raises complex issues for everyone in academia, and a sense of uncertainty about proper conduct in everything from admissions to recruitment to pedagogy and scholarly research. I have witnessed personally the abuse of cancel culture, on the one hand, and the smug denunciation of «wokeness» and affirmative action on the other. It is hard to get your bearings at this time, since one can be personally anti-racist, but professionally a beneficary of systemic racism. The old question, «what is to be done?» resonates throughout the halls of academe, and the halls of political institutions. My only answer is to continue in the long campaign for democracy, equality, and emancipation for all people – which is incredibly vague, but I hope informs the specific kinds of work I do with media and the arts.

Ö.A. To me it also seems interesting that none of your sources of inspiration are female – a circumstance which applies to my own sources of inspiration; and this interview is part of the work on my own epistemological paragons/demons. It would be interesting to hear how you attempt to overcome the underlying structures of your own epistemological implications and what you make of that.

W.J.T.M. In my long life, I have seen a transition in the humanities from a mostly all-male bastion into what is now a predominantly female profession. I think my formative influences were mostly male, especially those from the nineteenth century. But my contemporaries, those I have collaborated with as my work as author and editor matured, have actually been quite evenly divided between men and women. When I took over as editor of Critical Inquiry back in 1977, the editorial group was all male. My first priority was to bring in a female colleague as a co-editor. Elizabeth Abel (now at Berkeley) joined my small editorial group and immediately set out to document the first wave of academic feminism. Her special issue, Writing and Sexual Difference (1980) won numerous awards and actually inspired our first special issue on race. Henry Louis Gates, Jr., an untenured professor at Yale, wrote to me and proposed a sequel issue, Race, Writing, and Difference (1982).

As for my individual engagements, I think my scholarly work, beginning with my dissertation and first book, Blake’s Composite Art, pushed me into identification with the revolutionary, abolitionist forces of the French Revolution and the first emergence of feminist theory in the work of Mary Wollstonecraft. When coupled with the common causes of civil rights and the anti-war movement of the 1960s, I felt that my whole formation as an academic had been shaped by these political movements, and their contemporary descendants.

I should add that, as one who has lived in a primarily Black neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago for the last forty years, I understand that the Black community is not homogeneous. There are many differences of class and political positioning. The liberal reaction to «defund the police» in American cities divided the Black community down the middle, and it was, in retrospect, a deeply unfortunate slogan to march under when American politics is basically driven by slogans and four word commandments like «Make America Great Again.»

Ö.A. The opening chapter of your book Seeing Through Race is called «The Moment of Theory. Race as Myth and Medium,» and in it you unfold the basic theoretical ideas that run throughout the book and through the individual essays on the two topics of Black racialization and racialization in the Israel-Palestinian conflict. Your starting point can be found in the introductory chapter on page 13, where it says:

What I do hope to suggest, beyond these rather obvious issues, is to draw a somewhat less obvious conclusion from them: that race is not merely a content to be mediated, an object to be represented visually or verbally, or a thing to be depicted in a likeness or image, but that race is itself a medium and an iconic form – not simply something to be seen, but itself a framework for seeing through or (as Wittgenstein would put it) seeing as. This point is most explicit in the visual language of race, which continually invokes the figures of the veil, the screen, the lens, the face, the mirror, the profile, line and color, and its paradoxical fusion in the figure of the «color line» [...].5

«Race» is a medium we can’t get around. You therefore point to the persistence of «race as a political and economic issue, as well as a term linked to the all-too-durable phenomenon of racism».6 This is how I understand your effort: it does not seem to be an adequate solution to work on the erasure of «race», but it is necessary to understand how to deal with it, i.e. to work on «racism». Your chapter is very dense and the trains of thought traverse a thicket of discourses on racism theory as well as relationalizations of «race» and «racism» that seem counterintuitive (you don’t want racism to be understood as a derivative of «race» but reverse the relationship). I will not refrain from trying to ask you about a compression of your basic considerations.

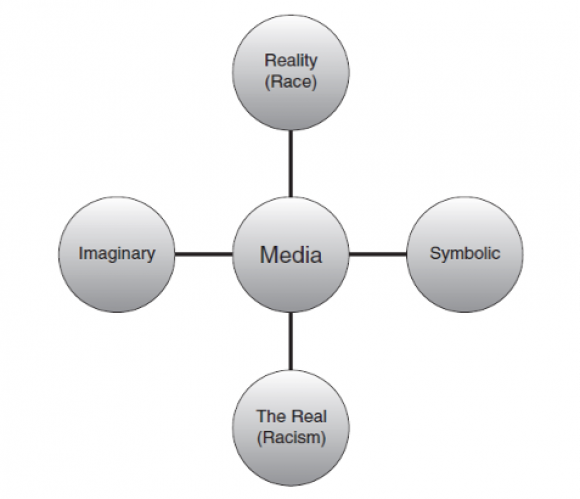

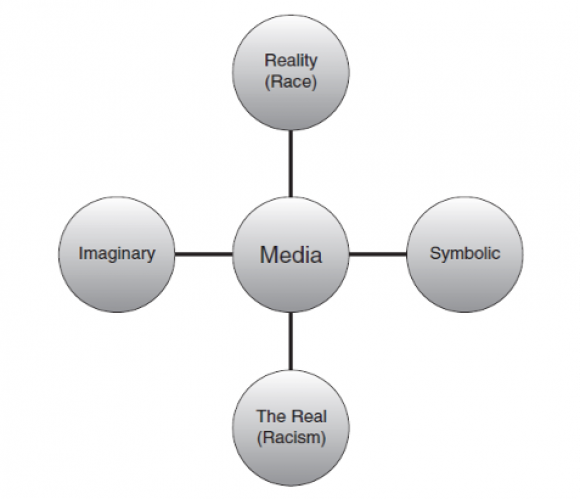

You explain «race» as a medium with the Lacanian model of the imaginary, symbolic and real and add «race» as the reality, where «racism» stands for the real. Connoisseurs of Lacan’s model know that subjectivation means entry into the symbolic and thus linguistic order and that the imaginary, the order of the image, forms another realm within which subjectivity becomes effective. The real, in turn, is the realm that escapes the order of language and image.

From Seeing Through Race (2012), p. 18: «The Lacanian registers, plus ‹reality›»

Can you briefly explain this model again, including «race» and «racism»? My aim here is to understand your commitment to media literacy, which will also address the questions that follow in a more concrete way.

W.J.T.M. I will try. Many different arguments are converging in this diagram, and it may be difficult to bring them all into focus without simply quoting from my book. The fundamental claim is fairly uncontroversial, namely that race is a «social construction,» a complex of verbal and visual constructions that constitute a mythology. My deviation from the so-called «post-racial» theorists is that I want to preserve the operational, pragmatic durability of that mythology. I reject the idea that race is «merely» a myth that we could banish by inserting it in quotation marks or excluding it from discourse. Even more emphatically, I want to question the goal of «color blindness,» as if we could re-train ourselves not to notice the visible and behavioral differences among groups of people who identify as kindred, or who have been identified (and persecuted) as members of the group.

At the same time, I think that certain kinds statements have to be assessed in a color-blind fashion, as independent of the racial identity of the speaker. A lie told by a Black or White person is still a lie. An incorrect solution to a mathematical problem by a Black or White student is still incorrect. Morality and mathematics are race-neutral, color-blind. I want us to be able to recognize, acknowledge, and appreciate racial identity as a key feature of human identity. At the same time, I want to resist any reductive essentialism that makes racial identity some sort of absolute and definitive account of anyone’s personhood. That is why I would never deny that I am a «white intellectual,» at the same time I would want to insist that my specific identity is not reducible to that label. I see whiteness as part of a «complexion» that includes much more than my skin color. And that complexion goes beyond my personal identity as well to include my identification by and with others.

Racism’s association with the Lacanian Real in this diagram is grounded in Jean-Paul Sartre’s discussion of Anti-Semitism as a passion attached to identity, a level of affect that links recognition with revulsion and hatred. That is why I see racial identity (which cannot be denied) as a kind of sublimation of racist emotions. If racism is the real pathology, the acceptance of race as a reality constructed by history and culture provides the possibility of a cure – perhaps on the model of inoculation and immunization. A simpler way of putting this might be to see race in affirmative terms. I was part of a white generation that learned to see that «Black is beautiful,» and that now allies itself with the Black Lives Matter movement. At the same time, we found ourselves in solidarity with folks who understood that race and racism were not simply a «black and white» issue, a moralistic reduction to good and evil. Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition, the growing acceptance of a multi-racial patchwork quilt of «complexions» has always struck me as the best hope for a healthy American democracy. Needless to say, this is not a done deal, and it is in real danger at a time when one of America’s political parties has become openly racist, and mounted an insurrection that brought the flag of the slave-owning Confederacy into the U.S. Congress.

Ö.A. In the German-speaking world the term «race» is historically very specific and not as usable as in the U.S.A. It was therefore particularly difficult to address the mechanism of racism in Germany, which is why discussions about racism in the German-speaking world were complexly conditioned and, for a long time, impossible to carry out productively. So, when you talk about «race» in your book, you are simultaneously talking about a way of using the term that does not exist in Germany and yet is practiced relentlessly, for example, even when talking about ethnicity or culture. I think that the latter term helps to better understand your arguments for the German-speaking world, even if it does not quite fulfil what «race» does. In this country we often talk about «cultural differences» and «other cultures». So even where «race» does not seem to appear, «race» is effective. You base this on the quality of «race» as a medium, which is closely linked to visual culture (see above) and is not just language, image, thing, representation.

We are, if I understand it correctly, already racist when we use the term «culture» in relation to groups of people, and I think it becomes immediately clear that any form of attribution of an identity to people and their grouping is necessary for speaking and for thinking (representation). Formulated differently and so perhaps closer to your thoughts: Racism is a form of thinking, of knowing, of seeing that presupposes «race» as immediacy, because any other thinking about people and groups of people is hardly possible. Your proposal is therefore a media pedagogical one: «We cannot seem to do without this concept, and we must conserve it for future uses that we can at this point only imagine. We must learn to see through, not with the eye of race».7

Who do you think has this ability to see «through race» and not with the «eye of race»? Or regarding our issue and suggestively asked: Are theoretically versed media scientists better equipped to see through race?

W.J.T.M. I don’t feel competent to comment on the German circumlocutions around the question of race and culture. But I do not think that we are «already racist» when we use the term «culture» to describe other groups of people. I think we are racist when we use culture as a euphemism to explain why others are backward, inferior, stupid, or dangerous, and therefore worthy of subjugation and discrimination. In the U.S., paradoxically, this has become a point of division between so-called «white folks.» What happens when a major political party forms an irrational cult of personality around a White supremacist who utters racist denunciations of all non-white peoples: Arabs, Latinos, Blacks, and even the «model minority» of Asians have been subjected to racist caricaturing by the former President of the United States. This has had the effect of reviving a deep current of American culture that dates back to the founding of the country as a slave-holding settler colony.

I don’t think media theorists are uniquely positioned to see this happening. A substantial majority of white folks across the political spectrum are appalled at this atavistic resurgence of racism and White Supremacy. The approaching crisis in American politics is a contest between the democratic ideals of the founders of the nation and the fact that all of them were slave-owners. (By the way, I do not favor tearing down statues of the founders for their ownership of slaves; Jefferson, Washington, Madison, Hamilton still deserve our respect). The U.S. is a nation founded in deep contradictions that have yet to be resolved, but which are quite different from those it confronted during the era of segregation and Jim Crow. My slender understanding of questions of race and culture in the German context would, I think, want to learn from the similar structural contradictions that divided Germany in a variety of ways during the twentieth century. It is striking to me that the nation that carried out the most appalling racist genocide in world history has recently welcomed multitudes of non-white, non-Christian immigrants into its borders. Germany has not resolved its contradictions either, but it could perhaps be a guide to the U.S. in recognizing them for what they are.

Ö.A. We, as editors of this issue, cannot share this view of Germany, since the necessity of, for example, postcolonial thinking and practices of decolonization are only just beginning. Currently, racist dispositions towards these «welcomed people» are enormous: The whole field of understanding and acknowledging racism suffered from the taboo of the word «race» that came after World War II. The fact that the word as such has become virtually unusable has, in my opinion, helped to prevent the necessary discussion of racism in Germany. Here, the word «Rasse» is too closely connected to the historical event of World War II, to discourses of biologism etc. Saying «racism» again in different discourses still feels very harsh here and many scholars and politicians try to avoid using it whilst looking for alternative terms. Having said that, the murder of George Floyd and the global attention the issue received also had an impact on the German situation. Some scholarly and other state initiatives have come to understand that there is still a lot of work to do in Germany in regards to racism. 8 In Germany there are almost no educational programs about cultural studies/dynamics of representation for schools (one can find such courses or content rather at universities); however, Germany is suffering from the circumstance of ignoring the racism that now reveals its «face» towards Muslims, Turks, Arabs, Sinti Roma, migrants from the Balkans (EU integration of Bulgaria, Romania etc.) and Asian and Black people and many others. Again: the racist discourse in Germany benefits from the word «culture» which is very often used to essentialize racial differences, so that racism is enabled and possible without thinking of «race» and «racism» at all.

To be more precise: Pointing to media scholars I wanted to understand whether this capacity to see through race corresponds with media literacy. Media studies in Germany ought to have a lot to say with regard to school curriculums, but we still lack educational programs that could help people to better navigate and see in the world (and thus find a strategy to deal with racism at a very young age). I understand your formula «seeing through race» as a claim that actually stands for the claim to understand media. This is why I want to know whether the issue of racism should be dealt with as an educational issue.

W.J.T.M. Yes, I think this is the correct approach. I don’t know that one has to insist on my «race as medium» formula, but I think it could be helpful, particularly in helping people understand how we tend to think with stereotypes, caricatures, and narratives of «the Other.» And perhaps the less loaded term of «culture» can be useful, especially when (in Germany) as you say, «Rasse» is such a loaded term that seems to block further conversation. It sometimes has that effect in the U.S. as well, and a lot has to do with who is using the word, and how. Recently I watched a debate between two Black male intellectuals discussing the tendency to portray Blacks as victims of racism, and to ascribe crime, poverty, etc. to white supremacy and white racism. Their disagreements were quite vehement, and I could see strong arguments on both sides, as issues of personal responsibility jostled against claims about systematic institutional bias. I think white folks need to enter into these discussions with tact and caution. The loud voices of certainty are the ones I tend to mistrust.

Ö.A. Your chapter begins with four quotations and the third of them is from Jacques Derrida’s White Mythology: Metaphor in the Text of Philosophy (1974). There it says: «What is metaphysics? A white mythology which assembles and reflects Western culture: the white man takes his own mythology (that is, Indo-European mythology), his logos – that is, the mythos of his idiom, for the universal form of that which it is still his inescapable desire to call Reason.» 9

Now your chapter just ends with a demand that is consistent with the white logos of reason: that we see through race and not embrace the eye of race. Isn't this contradictory, that the logos of reason that you also proclaim is on the one hand a white mythology, but on the other hand promises the solution to the problem it has itself actually created?

These considerations lead to an ambivalent relationship that is simultaneously tangential to your engagement as a white professor who speaks of race as a medium (and I don’t want to refuse the powerful capacity of this thinking as a «moment of theory» and the need to resist our pre-modern iconoclastic habits toward images; and you are surely aware of your positioning because you begin the book with a cautious positioning).

W.J.T.M. I would distinguish a fetishized version of Reason with a capital R, from reason as a key element of that complex formation known as human consciousness. One reason why, despite all its violent, evil history, the American Constitution continues to be an object of carefully measured idealization, is that it understood itself to be a modelled on a sane, self-governing complex of distinct powers and faculties. It has often amazed me that Black folks are ever patriotic about the United States, that in spite of everything, they continue to uphold the ideals of democracy, equality, self-governance that those slave-owning founders put into writing. This model was grounded in a picture of a mixed, healthy individual psychology, a balance of reason, judgment and will understood to correspond to legislative, judicial and executive powers.

So I see no contradiction between my wish to «see through race» and the exercise of reason, as long as reason is understood as one among the complex of faculties that constitute a healthy human consciousness. Empathy, compassion, judgment, and will are also necessary, along with a sense that reason as a purely isolated faculty (especially instrumental reason) is fully capable of making the trains of extermination run on time. William Blake’s character of Urizen (an allegory of Kant’s «pure reason»?) is an excellent reminder that rationality is not the equivalent of wisdom, and that it may serve to rationalize every sort of horror.

Ö.A. I think you are right in insisting on reason with a small r. I do not think that we have reached a state of reason that has taken into account its own affective dimension: I refer to Adorno & Horkheimer’s Dialektik der Aufklärung and the need to separate the senses so that «r»eason can be possible at all (the reference to the story of Odysseus and the Sirens). Many white people (I do not mean people with white skin) lack the experience of racialization. I think that a huge part of this reason you are describing requires that specific experiences remain outside because they are way too affective and too stressful for the senses so that it can continue to be the reason with a capital «R». So, when you are saying we have to «see through race» you actually mean that we are to set up a «healthy human consciousness» and consider all the virtues that come along with the issue of race.

I am curious to see how madness will add to this consciousness, as your next book will be on that issue. Maybe «seeing through madness» and «race» are very similar and yet a utopia of a way of seeing that we still haven’t reached so far?

W.J.T.M. Yes, there lies a dogmatism in reason with a capital «R» that, in the French Revolution, led to elevating a Goddess of Reason and the new rational «humane» form of mass execution provided by the guillotine. I advocate reason with a small r, as part of a complex and (hopefully) balanced human consciousness with multiple faculties.

Re: madness. This is a big question I am still struggling with. First, I think racism is a mental, emotional disorder grounded in paranoia, anger, and resentment that is frequently expressed in violent behavior. That is why I think of the concept of race as a potential homeopathic medicine for the pathologies of racism. People have to become conscious of racism, and it is hard for them to do this without recognizing that racial difference is built in to their perceptual frameworks. The idea of race allows acknowledgment of its psychological reality without giving in to the affective pathologies that contaminate it. It is like the Freudian maxim that one must acknowledge one’s condition before one can do anything about it.

But to me racism is only one among the many forms of mental disorder that afflict the human species (what we used to call the human race). Capitalism, as the unquestioned foundation of the modern economic system, is high on the list as well. The ideology of selfish individualism as a foundation for a good society seems to me a fundamental contradiction. The ideas that «growth» and «progress» and «economic development» are unquestionable values have to confront the accompanying destruction of habitats and the extinction of species. It is important to recognize that these are collective disorders or ideologies, and not merely individual psychological pathologies. So my history of madness emphasizes the way societies go crazy and embark on self-destructive patterns of behavior. In short, states can go mad, and the current rise of authoritarian regimes all over the planet is the most dramatic symptom of this. Democracy at this moment seems like an endangered species of political organization. Less dramatic, but equally dangerous in the long run, is the inability of states to come to a common agreement about climate change when the evidence that we are destroying our habitat is overwhelming. The legal definition of insanity in the U.S. is the judgment that someone «is a danger to oneself and others.» Surely this fits very well as a description of a species that is already wiping out numerous life-forms every day, and that belongs on the endangered species list to which it is contributing.

Ö.A. There is, after all, a difference of experience between white people and non-white people. The eye of racism does not hit the invisible white «crowd». This means that the vision of white people and racialized people must differ, as Frantz Fanon and others always emphasize. I think here from my point of view that the desire of the racialized is not to be seen, to be invisible like whites, and at the same time to be able to control one's own visibility between un/visibility, as only whites are rather capable of. When I am scanned by the police, I don't want to be seen, I want to remain invisible, but I do want to be visible as a person of color with recognition and dignity without being absorbed by «race». In your opinion, does this circumstance of «seeing» and «being» change anything in your models?

W.J.T.M. I would want to pluralize these differences of experience, to ensure that they include differences among white people as well as non-white people. Not a simple binary logic «between» White and non-White, but differences among a spectrum of colors. The Hispanic minority in the U.S., like the Black, is not monolithic, but includes a variety of languages, dialectics, and places of national origin. Invisibility as a racial issue would require a whole further elaboration of the visual field in relation to identity and identification. I think your question opens up the foundational paradox of identity, that we want to be recognized but not to be subjected to reductive, prejudicial classification. (This is why I resist being labelled a «white intellectual» as if it provided an infallible key to knowing what I am or what I think). We long for both visibility and invisibility, and finding the right balance is always an incomplete project. Ralph Ellison’s «invisible man» is simultaneously hyper-visible. The submerged racism in large portions of the U.S. population has lately become hyper-visible. And yet its tendency to reductive forms of reverse racism (stupid white men, rednecks, neo-nazis) carries its own dangers as well.

Ö.A. Now I am a bit surprised. When I speak of white and non-white, I am not referring to the dichotomy that you describe as «binary logic», but to the systemic structures or patterns that produce the field of normative invisibility, that produce another, ones to be devalued and excluded. Is it not the case, then, that seeing through race means not only acknowledging race as a medium, but also making visible that very field of invisibility that is constituted by Whiteness? I wonder, then, if the insights from Critical Whiteness Studies affect your theses. Or, to put it more sharply, it seems that the productive category of race is confronted with something that first and foremost produces this visibility of race. Doesn't seeing through race include making Whiteness visible?

W.J.T.M. I am having some difficulty tracking your argument here. You say that white/non-white is not a binary logic, but then you proceed with a series of binary oppositions between visibility/invisibility, Self and Other, white and non-white. I am not sure I know what Critical Whiteness Studies is. I do recognize a binary logic when I see it, and I think your questions tend to reflect it. My book resists quite explicitly the Black/White opposition as the only version of racial difference and antagonism. Anti-semitism is equally important, and it deploys figures of difference that tend to be non-visual. That is why I emphasize media and the mediation of racial difference as cultural complexes rather than some exclusively visual paradigm.

Yes, it is essential to make Whiteness visible, but also Blackness, Brownness, and don’t leave out Red and Yellow. I have always loved Sesame Street’s song by Kermit the Frog, «It’s Not Easy Being Green,» which plays upon the whole visibility/invisibility dialectic that is so foundational to the perception of race. That is what led me to the intuition that race is best considered as a medium (and not just a visual medium) in the first place. And it is why the mandate to be «color blind» always struck me as a false solution to the problem of racism. The difficult task we have as educators is to cultivate racial consciousness without producing a disabling self-consciousness and useless forms of white guilt that prevent authentic, spontaneous relations between people with different racial identities. There is no substitute for face-to-face interaction and friendship. Human beings—and especially White people--have spent a very long time inhabiting the nightmare of racism and racial prejudice. Waking up from that nightmare, the project of «wokeness,» cannot be accomplished by snapping one’s fingers or issuing an edict. In fact, wokeness has a deeply pathological component that induces virtue signaling, cancel culture, and the patronizing of non-white persons as nothing but victims. One regrettable consequence of wokeness is its tendency to attribute infallible authenticity to the feelings of non-white people. One sees this in the invocation of subjective «experience» as a kind of epistemological guarantee of unquestioned certainty.

Ö.A. Critical Whiteness Studies and Critical Race Theory are becoming more and more popular in German-speaking countries; the topic of racism has become more and more anchored in the public sphere, and increasingly heated debates are also taking place outside the USA. What would you like to add since the publication of your book Seeing Through Race, or how would you comment on your book today? How would you describe your relationship to the book, and the book itself, in terms of developments since then?

W.J.T.M. The reaction against Critical Race Theory (CRT) in the U.S. is very powerful and wide-ranging. Of course, the opponents of CRT know very little about what it involves. Their opposition amounts to disavowal and denial of the plain facts of history and sociology. The thing I am struggling with since my book was published is the emergence of so-called «cancel culture» in the American academy. It has taken on an exaggerated importance in some quarters. Just yesterday, one of my colleagues in climate science at the University of Chicago had his lecture at M.I.T. cancelled because of his public criticisms of affirmative action as a way of patronizing minorities in the academy. The rhetoric of free speech and claims to being harmed by speech seem to be escalating on every side. When I recently exhibited the photograph of the «Hooded Man of Abu Ghraib,» a victim of the U.S. torture regime in Iraq, an Arab student objected that showing the image has the effect of humiliating Arabs. My response was that the image is thoroughly contextualized in my exhibition, and is shown as an indictment of the American invasion, not an endorsement of the practices it revealed. But I have to admit that one of the main subjects of your interest in my work has now become problematic for my own pedagogy. I am referring to Spike Lee’s film, Bamboozled, which I regard as a masterful critique of American racism, but one that I had to admit was «fifty years ahead of its time.» I would hesitate now to show his film in my classes because I would immediately expose myself to the charge of using my white privilege to play a film that is a catalogue of Jim Crow stereotypes and «coon» humor. I saw Spike Lee’s film as a «message in a bottle» for a time when it would be possible to see it without being wounded. Perhaps my own book, Seeing through Race, is also a message in a bottle. It was great to present my theses on the occasion of the W. E. B. Dubois Lectures at Harvard, but I am unsure about their timeliness today, when the passions of racism and anti-racism are threatening American democracy.

Ö.A. I also find these forms of refusal to communicate and boycotts, which can be violent, very alarming. We have to be aware of the instances of enunciation and I think that in this heated atmosphere people very often mix up these instances of enunciation (presenting Bamboozled does not mean to fix stereotypes because one shows it etc.).

But what does cancellation really mean? Is it really the case that this professor cannot speak at all at the university anymore? What about the communication that followed after the reaction of the professor?

For me, the moment of cancel culture is something else: these refusals often represent representative political acts, which try to update historicity and injustice and (I find this rather difficult) to compensate by powerfully haunting the field of communication and proclaiming «It can't go on like this». So, if I understand these dynamics correctly, it is also about repairs that could have been implemented before, but which simply did not happen because privilege is not waived on the part of the existing (white) circumstances. This is one reason why there is rather less mercy and more «cancelling» in the field. The question to me is whether such possibilities of privilege waiver are systemically possible in such a way that they also lead productively into the direction of a society worth living in. How is such a waiver possible and can it be shaped in such a way that it leads to a more solidary social structure? So, I personally think that, in addition to media skills, it will be especially about those values that also co-constitute your model of a reason: empathy, passion, judgment – and forgiveness.

W.J.T.M. I agree that cancel culture sees itself as an attempt to undo historical injustices. But it has a tendency to express itself in counter-productive forms of performative politics (e.g., «Defund the Police»). I have recently witnessed a Black performance artist throwing a tantrum because a white composer included the Negro spiritual «O Freedom» in a composition that surveyed the art of protest music across a variety of traditions. The claim was that only Black musicians can play Black music, and that for a white musician to play a Black piece was an act of cultural theft and appropriation. This strikes me as dangerous nonsense, and the more passionately and loudly it is expressed, the more my resistance is aroused. It becomes even more toxic when well-meaning white folks fall into this trap, and assuage their aroused feelings of white guilt by parroting cliches of racial essentialism that verge on calls for re-segregation. As for the «waiving» of white privilege, I am not certain what this would mean or how it would be done. Is it really up to individuals to waive something that is baked into the societies they inhabit? Or is this more like «waving the flag» of anti-racism to signal one’s virtue without doing much of anything.

Ö.A. We thank you for your answers and for taking the time!

On behalf of the editors of this issue

Ömer

- 1W.J.T. Mitchell: Seeing Through Race, Cambridge (MA), London 2012.

- 2Occasionally, in some contexts, it is referred to as Visual Culture Studies. For more, see Margaret Dikovitskaya: Visual Culture: The Study of the Visual after the Cultural Turn, Massachusetts 2005, and Marquard Smith: Visual Culture Studies: Interviews with Key Thinkers, London 2008.

- 3Cf. Susanne von Falkenhausen: Beyond the Mirror. Seeing in Art History and Visual Culture Studies, Bielefeld 2020.

- 4I got into this conflict earlier in my career Unaware of what was happening between feminist, hegemony-critical visual culture and male-hegemonic visual studies, I had suggested a translation of Mitchell’s critical text on Spike Lee’s racism satire Bamboozled (2000) to a well-known feminist journal. I wanted to translate it because the essay had not been integrated into the German-language translation of W.J.T. Mitchell’s book What Do Pictures Want (2005). To me, the text seemed astonishing and important and I was hopeful that I could draw the attention of media scholars to the issues (and to myself as well). I never received a response from the journal editors, which demotivated me as a marginalized, immigrant young scholar from a working-class household. That I wanted to translate Mitchell, a representative of a male-dominated image science, had to lead to a rejection – and were that rejection to have been communicated to me, I would have understood it – but we all know that we are always victims of rejections, and of the ignorances of the system, that can destabilize our self-esteem as scholars. I would have liked the editors to be sensitive to such a request, that is, that there should be a special sensitivity towards requests from young scientists’ scholars in general and that this should be part of a feminist critical sensitivity; access of people of color to the world of media studies is not easy. I am very pained to mention this anecdote, which in itself reveals an accusation, as I see myself in solidarity with feminist struggles in academe, and perhaps it was just a faux pas on the part of the editors not to have replied to me (although I did follow up at least once). Nevertheless, I feel I must relate it. It points to the traumatizing double bind of racist mentalization, by which I mean the psychological burden of not being allowed to assume racist intentions in order to protect one’s counterpart or even to be fair, but nonetheless enduring the consequences of the counterpart’s possible intentions or their simple lack of awareness. Eventually, I was able to publish the translation of Mitchell’s text in my anthology Deutsch-Türkische Filmkultur im Migrationskontext (German-Turkish Film Culture in the Context of Migration, 2017) and to comment on it comprehensively with regard to the racist/migration/cultural situation in the German-speaking world. That I was able to publish this anthology at all, I owe to the scholarship foundation Avicenna Studienwerk e.V., a Muslim funding organization that is financed by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), whose mentors initiated me into the practice of editing, and helped me break through the gate-keeping that had occurred up to that point.

- 5Mitchell: Seeing Through Race, 13.

- 6Ibid., 22.

- 7Ibid., 40.

- 8Cf. Federal Anti-Discrimination Agency: ECRI-Report: Germany needs to make greater efforts against racism, March 17, 2020, https://www.antidiskriminierungsstelle.de/SharedDocs/pressemitteilungen/EN/2020/20200317_ECRI_Bericht.html (April 4, 2022).

- 9Quoted in Mitchell: Seeing Through Race, 7.

Bevorzugte Zitationsweise

Die Open-Access-Veröffentlichung erfolgt unter der Creative Commons-Lizenz CC BY-SA 4.0 DE.