Circulation Revisited

A Forum on the Actuality of the Concept. Comment by Lisa Parks

The German version of this text has been published here.

The Zeitschrift für Medienwissenschaft no. 23 focuses on media and technologies of circulation in waste, computer simulation, festivals, migration, and data. In addition to the original articles in the issue, we have invited established scholars who have used, criticized or historicized the notion of circulation. We wanted to know how they think about the following questions:

- In which ways did your object of study prompt you to think about or use the concept of circulation?

- How do you address the prevalent implications in the notion of circulation regarding question of openness and closure, channelled flows and infrastructure, as well as the mediality of observation?

- What would you miss if you gave up the notion of circulation? What is the biggest challenge for further research on circulation?

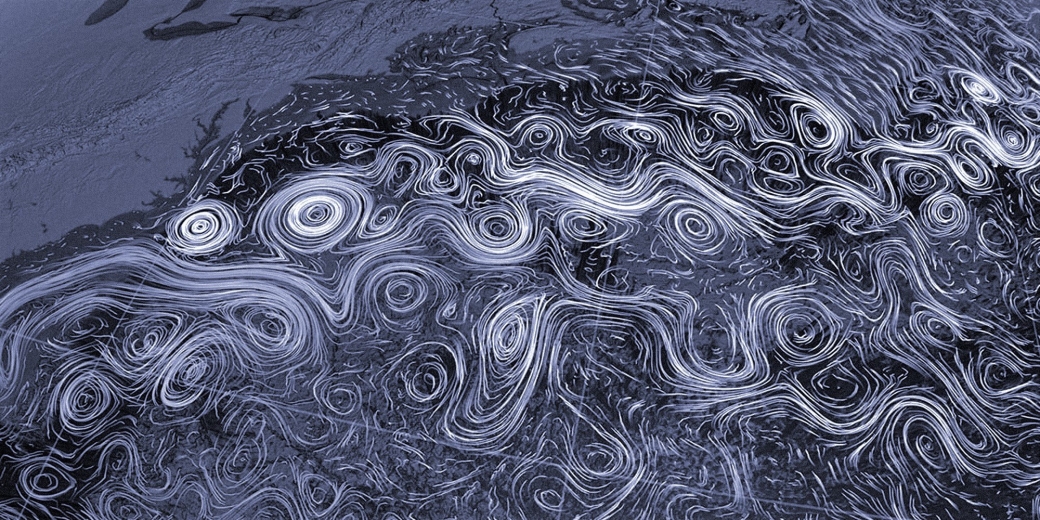

My past research on satellite technologies and media infrastructures prompted me to think about the concept of circulation in relation to the physical distribution of audiovisual content. In a book I co-edited with, Nicole Starosielski1 we used the term «signal traffic» to explore how physical infrastructures and technical artifacts, including transoceanic cables, cell phone towers, broadcast transmitters, and satellites, are organized to circulate media content. We used the word distribution in the book, however, more than circulation, because we were interested in encouraging media research that moved move beyond analyses of production and consumption. The word circulation implies a cycle or a return; we were more focused on the departures and arrivals of media signals, and in critical examination of the materialities of media distribution. In U.S.-based media studies the connotative meanings of distribution are often linked to Marxist economic theory and materialism, while circulation, to my mind, is articulated more with structural linguistics, semiotics, and signs. With the emergence of smart media, logistical media, and automated media, however, the meanings of the term circulation are shifting yet again. The conceptualizations of circulation that have most influenced my research and thinking come from Michel Foucault’s writings about power (1977; 1980)2 and governance (2007).3 Foucault conceptualizes power as a kind of a circulatory system, and such ideas have inspired me to think about how media power moves and where it settles, and how that process reshapes environments and social relations. Also, rather than think of power as a given Foucault urges us to recognize it as a set of potentials, possibly even including reversals. Power can be concentrated in particular sites (governments, institutions, companies) yet it is also, as Foucault suggests, always dispersed, and as such transits through and shapes bodies and practices. Even as states attempt to administer populations and secure territories using particular techniques of power and control, all bodies participate in the circulation and maintenance of power relations. The concept of power as circulation, then, prompted a recognition of the need to study and analyze distributed, even unwieldy, and unpredictable biopolitical formations. These ideas from Foucault played a vital role in motivating my interest in researching media infrastructures. I have been more interested in trying to glimpse and understand processes of media dispersions than in trying to master media concentrations. Some of Foucault’s writings use the word circulation in ways that conjure up more literalized infrastructural processes. For instance, the term comes up in his discussions of the governance and management of resources and essential services. This, according to Foucault, is a matter of «controlling circulation. Not the circulation of individuals but of things and elements, mainly water and air…The problem of the respective position of fountains and sewers, the pumps and river washhouses…How to prevent the infiltration of dirty water into the drinking water fountains…How to keep the population’s clean water supply from being mixed with the waste water.»4

1. In some ways, I am interested in the mediatic equivalent of this hydrographic mapping. For instance, how do transmitters, data centers, or cell towers physically direct the flow of media content? What resources, labor, and organizations are involved? As I engage with such questions, I do not idly embrace the metaphor of «flow».5 In fact, much of my recent research has been about disruptions of media flows –dis-connections, failures, and shutdowns6–or moments in which circulation fails. These moments define most peoples’ experiences of contemporary media in the world, since most do not live in conditions of energy and digital affluence and abundance. It is through instances of scarcity, breakdowns and bottlenecks that the power to know and control media and information technologies becomes redistributed; machinic understanding emerges through acts of jerryrigging to capture a signal, device disassembly, temporary fixes, and repair. These instances are not rare or incidental but are, in fact, integral to and constitutive of media circulation. Circulation is only salient as a concept in media studies if maintenance and repair are built into it.

2. I address these issues by thinking about the material infrastructures through which media content or signs circulate. Media content does not move around magically; there are specific technical artifacts, labor relations, and systems that have been organized and put into place to facilitate their circulation, whether as signals or data. By recognizing and studying the sociotechnical relations that constitute media infrastructures, it is possible to understand circulation as a goal or aspiration rather than a reality. While circulation certainly occurs, it does not occur in total, uninterrupted, or unchallenged ways. Thus, it is important to modulate understandings of circulation with languages and experiences of disconnection, malfunction, broken circuits, and so on. It is also crucial to consider issues of scale. As your question implies, it is not possible for a human to witness entire routes of media circulation, especially in a global context. Circulation presents problematics for documentation, record-keeping, and cartography, and for researchers in media studies. What does the circulation of a social media post look like on the back end? Where did it originate? Which computers, data centers, and cables was it routed through? Was it reviewed by a content moderator? Where did it end up? In order to answer these questions one also would need to consider the role of automation and AI in facilitating or preventing this circulation.

3. Although I was inspired by Foucault’s writings and use of the concept of circulation, I do not feel wedded to it, particularly given the term’s anthropogenic associations. I tend to use the concept of distribution more when discussing the transmission or movement of media content. Other verbs have also emerged as synonyms, whether flow, networking, trafficking, or, in the case of satellites, beaming. The biggest challenge for further research on circulation is to crack the circuit – that is, to not get caught in critical feedback loops and tautologies that involve studying circulation for circulation’s sake. Having said this, it is crucial that media scholars further explore how circulation is implicated in the emergence and sustenance of smart systems, surveillance, and algorithmic media. These media are premised on automated continuities, cyclical patterns, predictive analytics, and convenient looped efficiencies. Given this, the critical question may become: how to intervene in or purposefully disrupt circulation?

References

Foucault, Michel. 1977. Discipline and Punish: the Birth of the Prison. New York: Pantheon Books.

Foucault, Michel. 1980. History of Sexuality Volume I: An Introduction. New York: Vintage.

Foucault, Michel. 2007. Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the College De France, 1977-78. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Foucault, M. 2000. The Birth of Social Medicine. In Power: Essential Works of Foucault 1954–1984. Vol. 3, edited by J. Faubion, 134–156. London: Allen Lane.

Pereira, Gabriel, Iago Bojczuk, & Lisa Parks. 2020. WhatsApp Disruptions in Brazil: A content analysis of user and news media responses, 2015-2018, in: Global Media and Communication Journal, forthcoming.

Parks, Lisa and Nicole Starosielski, eds. 2015. Signal Traffic: Critical Studies of Media Infrastructures. Champaign-Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Parks, Lisa 2016. Reinventing television in rural Zambia: Energy scarcity, connected viewing, and cross- platform experiences in Macha, Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 22(4), 440-460.

Parks, Lisa & Rachel Thompson. 2020. The Slow Shutdown: Information and Internet Regulation in Tanzania from 2010 to 2018 and Impacts on Online Content Creators, International Journal of Communication, forthcoming.

Williams, Raymond. 1975. Television: Technology and Cultural Form. New York: Schocken Books.

- 1Parks, Lisa and Nicole Starosielski, eds. 2015. Signal Traffic: Critical Studies of Media Infrastructures. Champaign-Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- 2Foucault, Michel. 1977. Discipline and punish: the birth of the prison. New York: Pantheon Books; Foucault, Michel. 1980. History of Sexuality Volume I: An Introduction. New York: Vintage.

- 3Foucault, Michel. 2007. Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the College De France, 1977-78. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- 4Foucault, M. 2000. «The Birth of Social Medicine». In Power: Essential Works of Foucault 1954–1984. Vol. 3, edited by J. Faubion, 134–156. London: Allen Lane.

- 5Williams, Raymond. 1975. Television: Technology and Cultural Form. New York: Schocken Books.

- 6Parks, Lisa 2016. “Reinventing television in rural Zambia: Energy scarcity, connected viewing, and cross- platform experiences in Macha,” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 22(4), 440-460; Parks, Lisa & Rachel Thompson. 2020. «The Slow Shutdown: Information and Internet Regulation in Tanzania from 2010 to 2018 and Impacts on Online Content Creators», International Journal of Communication, forthcoming; Parks, Lisa & Rachel Thompson. 2020. «The Slow Shutdown: Information and Internet Regulation in Tanzania from 2010 to 2018 and Impacts on Online Content Creators», International Journal of Communication, forthcoming.

Bevorzugte Zitationsweise

Die Open-Access-Veröffentlichung erfolgt unter der Creative Commons-Lizenz CC BY-SA 4.0 DE.