Circulation Revisited

A Forum on the Actuality of the Concept. Comment by Stephen Collier

The German version of this text has been published here.

The Zeitschrift für Medienwissenschaft no. 23 focuses on media and technologies of circulation in waste, computer simulation, festivals, migration, and data. In addition to the original articles in the issue, we have invited established scholars who have used, criticized or historicized the notion of circulation. We wanted to know how they think about the following questions:

- In which ways did your object of study prompt you to think about or use the concept of circulation?

- How do you address the prevalent implications in the notion of circulation regarding question of openness and closure, channelled flows and infrastructure, as well as the mediality of observation?

- What would you miss if you gave up the notion of circulation? What is the biggest challenge for further research on circulation?

To begin with your first question, I don’t think I have ever «used» the concept of circulation. Instead, my projects have investigated the way that historically (and otherwise) situated actors constituted circulation as an object of knowledge and a target of intervention. To be a bit more specific: my work has examined the genealogy of modern governmental rationality in various problem-domains – Soviet planning and social welfare, economic management and mobilization planning in the U.S., preparedness and resilience planning, etc. In all of these domains, circulation appears as a key practical and conceptual terrain of modern government.

From this perspective, and now I am addressing the second question, the interesting point is not whether the concept of circulation brings along some inherent meanings of closure, circularity, or immobility. Rather – and here I borrow a formulation from Ute Tellmann – circulation emerges again and again as a privileged site where we can observe how the political and the economic are divided and thereby constituted in liberal government, in some cases at the limits of liberal government. An obvious starting point here is Foucault’s discussion of circulation in distinguishing the disciplinary controls of classical monarchy from the doctrine of laissez faire that he found in the Physiocrats and in early liberalism. What was at stake in this distinction was not just a new strategy for dealing with familiar problems such as food supply or town planning, but the emergence of what he called a new «political personage»: the population or society as the natural-technical object of government. For the Physiocrats and early liberals, circulation is the thing you have to leave alone, or enable through the light touch of regulation, material supports, or a framework of law, but not directly dictate. My work has addressed the other side of this story: how planners, officials, experts and others concerned with the limits to laissez faire, invented modes of governmental intervention not just to ensure circulation in general, but to ensure certain kinds of circulation, directed to certain substantive ends.

I first dealt with these themes in my book Post-Soviet Social. There, I showed that early Soviet planning involved disciplinary control over circulatory flows. But it directed them to a distinctively modern object: the national economy, conceived as a vast system of inputs and outputs, in which one had to maintain balance (of materials, labor, energy, etc.). This project was explicitly located at the limits of laissez faire, as Soviet planners understood it. The Soviets say: you, in the rich countries that are the centers of imperial power, can tell yourself fables about naturalness and self-regulation, but we, the backward countries, the victims of imperialism, have to control and enclose circulation, and direct it to our purposes. The initial instrument of this project was a massive electrification campaign, which involved building both generating facilities (dams, power plants, and so on) and a transmission grid whose specific geography defined the early pattern of Soviet industrialization and urbanization. So, this disciplinary control of circulation was directed to specific substantive aims: electric power delivered to certain places to industrialize the country, to provision new urban residents, in a broader project of national development.

My book with Andrew Lakoff, The Government of Emergency, investigates circulation as a privileged conceptual-practical terrain in American liberal government. We trace how a project for governing circulation initially assembled in city and regional planning – which described cities as organisms with circulatory or nervous systems of transportation, communication, and electricity flow – migrated to the Federal Government in the 1930s. This development is central to the governmental rationality of the New Deal, which is underpinned by a whole set of concepts and practices for knowing and managing the circulation of money and things: interdependency, flow, velocity, inventories, stocks, multipliers, production coefficients, propensities to save and consume. In the late 1930s, these elements were redirected to industrial mobilization for World War II. Mounting government expenditure on military production introduced all kinds of problems: bottlenecks, shortages, and so on. New Deal planners working in the wartime mobilization agencies invented a system for managing the circulation of resources through the entire American industrial economy. It isn’t a Soviet-style system of disciplinary control because it operates through incentives and contracts with private producers, along with control over allocation. Indeed, this distinction was hugely important because there is a whole issue of how to run a wartime economy without destroying American economic institutions. This point, by the way, has been somewhat missed by proponents of a Green New Deal based on the model of wartime mobilization—it involved a massive accommodation to corporate power, so it isn’t a very good reference point for a purist project on this score. But the point here is that, again, we find a project for governing circulation that is constituted at a limit of laissez faire, but now to preserve a system of free enterprise even as the government organizes totally unprecedented forms of intervention.

The central focus of The Government of Emergency, however, is something else. We show that the same techniques invented for governing circulation during the Great Depression and total war were redeployed in the early Cold War to assess the likely effects of an enemy attack on American vital circulatory systems, and to lay plans to ensure their continuous operation in the wake of such an event. As early as 1946, American specialists and planners begin to refer this problematization of circulation as a matter of «resilience».

An important point about these early discussions of resilience in the 1940s and 1950s is that the idea was not to just maintain the system of circulation that existed before. Rather, resilience implied adaptive adjustment to novel situations. In general, planners of the early Cold War – and it is notable that many of the relevant figures were economists who had worked in wartime mobilization—saw the market as the appropriate mechanism through which adaptive adjustment to new circumstances was organized in a free enterprise economy. But «resilience» referred to a different kind of situation: a shock that broached a limit where market mechanisms needed to be directed to certain ends rather than others, or replaced by purposive intervention. So, preparedness means that, in the aftermath of a military attack, you will be ready to reequip and repurpose key facilities, draw on stocks, curtail some activities while directing limited resources to others, substitute one resource or process for another. It also means identifying functions that will be essential following such an event and being ready to ensure and secure the circulatory flows required to sustain them, whether that means inputs for industrial processes or food production, or trained personnel, medicine, hospital capacity, and medical equipment.

One payoff of this kind of genealogical analysis that focuses our attention on circulation as a privileged terrain of modern governmental rationality is that it allows us to make sense of the way that certain contemporary problems are formulated and managed. Think, for example, of the ongoing governmental response to the COVID outbreak, which is all about circulation and, in particular, about resilience as a way of governing circulation. On the one hand, we see an attempt to shut down dangerous circulation that would lead to further spread of disease—a policy of disciplinary control that dates at least to the quarantines of the 14th or 15th centuries. But the aim of this practice is thoroughly contemporary: to prevent health infrastructure from being overwhelmed. To «flatten the curve» is to avoid bottlenecks and shortages. And alongside the quarantine we see a whole series of other techniques invented for governing circulatory flows in the early contexts of depression, war and Cold War: drawing on stocks and inventories, production controls, the construction of additional facilities, and so on. At the same time, a central part of COVID response has been keeping “essential activities” of the economy operating in the context of a health emergency. This also is a matter of governing circulation, ensuring certain kinds of circulation while suppressing others. These practices for governing circulation cannot readily be understood either in terms of the self-adjustment of the economic system or, on the other hand, in terms of a governmental takeover. Rather, resilience, as a mode of governing circulation in emergency situations, divides up the political and the economic in distinct ways.

This focus on circulation – again as a register of governmental knowledge and practice, and not as a second-order analytical category – also offers a distinctive kind of critical purchase on key terms of contemporary government. I have written on this point in relation to neoliberalism, but here let me indicate what I mean by staying with this example of resilience. Some scholars have traced contemporary resilience to particular thinkers like Hayek and Holling, and then arrived at a broad diagnosis – that, for example, resilience is a program of dealing with shocks and crises through laissez faire of some distinctive contemporary variety that is worked through the post-war information sciences. To my reading such analysis commits a sort of genetic fallacy in finding essence in origins. It also ontologizes the political and the economic, treating them as sort of primary categories of existence to which a governmental rationality like resilience assigns things. By contrast, a focus on circulation situates us at the level of practices, and concrete spatial and material arrangements, and allows us to consider how specific programs of governing divide up and thereby constitute the political and the economic.

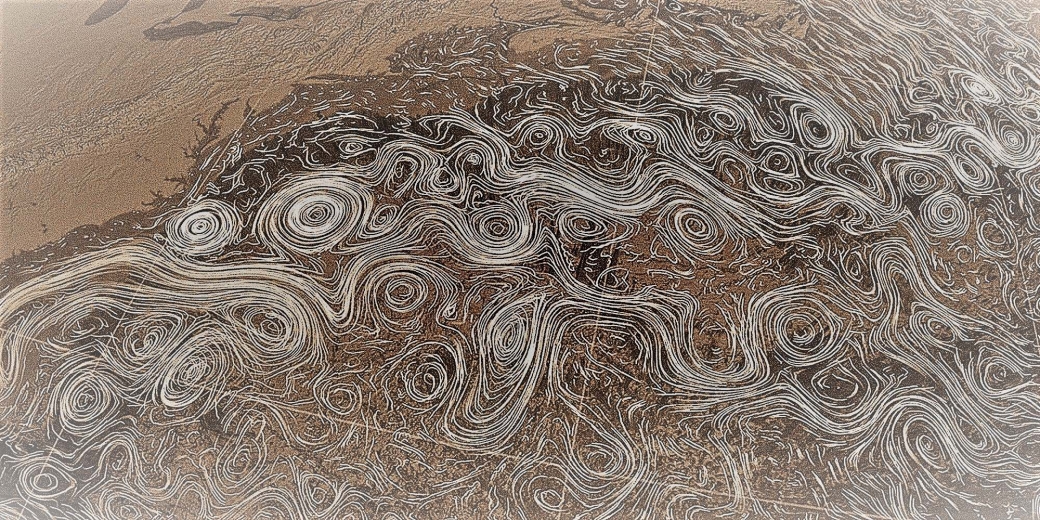

As an illustration, some of my recent work has been on urban resilience planning, much of it focused on systems of circulation: water, electricity, finance, etc. In California, much of the population lives in arid or seasonally arid areas, and relies on vast circulatory systems that capture, store, and distribute water. But the balance of this circulatory system is threatened by growing extremes of drought and by warming temperatures that will reduce the size of the snowpack in the mountains, an enormous stockpile of water that allows this system to deal with inter-seasonal variations in rainfall. So, water supply is a key vulnerability that many urban resilience and adaptation plans address. For example, Los Angeles has recently developed a plan to localize the water system. This plan proposes to build hundreds or thousands of green infrastructure installation – rain gardens, bioswales, other permeable treatments – to recharge a massive aquifer under the city. The idea is to create a closed loop of rain and stream capture, storage, consumption, and treatment within the metropolitan area to reduce the city’s exposure to the disruption of large-scale circulatory systems, and better able to deal with local rainfall variation.

This proposed system of circulation interacts with choices of all kinds of market actors –both individuals and firms. But it constitutes the adaptive transformation of this circulatory system as first of all a site for government intervention and collective action. It thereby frames a whole series of political problems – structures a political terrain. What benefits or costs will be entailed by the installation of green infrastructure elements, which are at once part of a large circulatory system and interventions in a particular place, with local costs and benefits? How will these be distributed? How does this system of circulation map on to political jurisdictions? Who is in and who is out? What would it mean if a massive urban area like L.A. seceded in large part from the California water system, in which urban users cross-subsidize rural users, mostly to the benefit of large-scale agribusiness? Once we free ourselves from trying to find the hidden workings of a radical market project or whatever else as the deep truth of resilience initiatives, and instead focus on the level of practices and particular spatial and material arrangements, innumerable specific sites of politics and very concrete political stakes come into focus.To begin with your first question, I don’t think I have ever «used» the concept of circulation. Instead, my projects have investigated the way that historically (and otherwise) situated actors constituted circulation as an object of knowledge and a target of intervention. To be a bit more specific: my work has examined the genealogy of modern governmental rationality in various problem-domains – Soviet planning and social welfare, economic management and mobilization planning in the U.S., preparedness and resilience planning, etc. In all of these domains, circulation appears as a key practical and conceptual terrain of modern government.

From this perspective, and now I am addressing the second question, the interesting point is not whether the concept of circulation brings along some inherent meanings of closure, circularity, or immobility. Rather – and here I borrow a formulation from Ute Tellmann – circulation emerges again and again as a privileged site where we can observe how the political and the economic are divided and thereby constituted in liberal government, in some cases at the limits of liberal government. An obvious starting point here is Foucault’s discussion of circulation in distinguishing the disciplinary controls of classical monarchy from the doctrine of laissez faire that he found in the Physiocrats and in early liberalism. What was at stake in this distinction was not just a new strategy for dealing with familiar problems such as food supply or town planning, but the emergence of what he called a new «political personage»: the population or society as the natural-technical object of government. For the Physiocrats and early liberals, circulation is the thing you have to leave alone, or enable through the light touch of regulation, material supports, or a framework of law, but not directly dictate. My work has addressed the other side of this story: how planners, officials, experts and others concerned with the limits to laissez faire, invented modes of governmental intervention not just to ensure circulation in general, but to ensure certain kinds of circulation, directed to certain substantive ends.

I first dealt with these themes in my book Post-Soviet Social. There, I showed that early Soviet planning involved disciplinary control over circulatory flows. But it directed them to a distinctively modern object: the national economy, conceived as a vast system of inputs and outputs, in which one had to maintain balance (of materials, labor, energy, etc.). This project was explicitly located at the limits of laissez faire, as Soviet planners understood it. The Soviets say: you, in the rich countries that are the centers of imperial power, can tell yourself fables about naturalness and self-regulation, but we, the backward countries, the victims of imperialism, have to control and enclose circulation, and direct it to our purposes. The initial instrument of this project was a massive electrification campaign, which involved building both generating facilities (dams, power plants, and so on) and a transmission grid whose specific geography defined the early pattern of Soviet industrialization and urbanization. So, this disciplinary control of circulation was directed to specific substantive aims: electric power delivered to certain places to industrialize the country, to provision new urban residents, in a broader project of national development.

My book with Andrew Lakoff, The Government of Emergency, investigates circulation as a privileged conceptual-practical terrain in American liberal government. We trace how a project for governing circulation initially assembled in city and regional planning – which described cities as organisms with circulatory or nervous systems of transportation, communication, and electricity flow – migrated to the Federal Government in the 1930s. This development is central to the governmental rationality of the New Deal, which is underpinned by a whole set of concepts and practices for knowing and managing the circulation of money and things: interdependency, flow, velocity, inventories, stocks, multipliers, production coefficients, propensities to save and consume. In the late 1930s, these elements were redirected to industrial mobilization for World War II. Mounting government expenditure on military production introduced all kinds of problems: bottlenecks, shortages, and so on. New Deal planners working in the wartime mobilization agencies invented a system for managing the circulation of resources through the entire American industrial economy. It isn’t a Soviet-style system of disciplinary control because it operates through incentives and contracts with private producers, along with control over allocation. Indeed, this distinction was hugely important because there is a whole issue of how to run a wartime economy without destroying American economic institutions. This point, by the way, has been somewhat missed by proponents of a Green New Deal based on the model of wartime mobilization—it involved a massive accommodation to corporate power, so it isn’t a very good reference point for a purist project on this score. But the point here is that, again, we find a project for governing circulation that is constituted at a limit of laissez faire, but now to preserve a system of free enterprise even as the government organizes totally unprecedented forms of intervention.

The central focus of The Government of Emergency, however, is something else. We show that the same techniques invented for governing circulation during the Great Depression and total war were redeployed in the early Cold War to assess the likely effects of an enemy attack on American vital circulatory systems, and to lay plans to ensure their continuous operation in the wake of such an event. As early as 1946, American specialists and planners begin to refer this problematization of circulation as a matter of «resilience».

An important point about these early discussions of resilience in the 1940s and 1950s is that the idea was not to just maintain the system of circulation that existed before. Rather, resilience implied adaptive adjustment to novel situations. In general, planners of the early Cold War – and it is notable that many of the relevant figures were economists who had worked in wartime mobilization—saw the market as the appropriate mechanism through which adaptive adjustment to new circumstances was organized in a free enterprise economy. But «resilience» referred to a different kind of situation: a shock that broached a limit where market mechanisms needed to be directed to certain ends rather than others, or replaced by purposive intervention. So, preparedness means that, in the aftermath of a military attack, you will be ready to reequip and repurpose key facilities, draw on stocks, curtail some activities while directing limited resources to others, substitute one resource or process for another. It also means identifying functions that will be essential following such an event and being ready to ensure and secure the circulatory flows required to sustain them, whether that means inputs for industrial processes or food production, or trained personnel, medicine, hospital capacity, and medical equipment.

One payoff of this kind of genealogical analysis that focuses our attention on circulation as a privileged terrain of modern governmental rationality is that it allows us to make sense of the way that certain contemporary problems are formulated and managed. Think, for example, of the ongoing governmental response to the COVID outbreak, which is all about circulation and, in particular, about resilience as a way of governing circulation. On the one hand, we see an attempt to shut down dangerous circulation that would lead to further spread of disease—a policy of disciplinary control that dates at least to the quarantines of the 14th or 15th centuries. But the aim of this practice is thoroughly contemporary: to prevent health infrastructure from being overwhelmed. To «flatten the curve» is to avoid bottlenecks and shortages. And alongside the quarantine we see a whole series of other techniques invented for governing circulatory flows in the early contexts of depression, war and Cold War: drawing on stocks and inventories, production controls, the construction of additional facilities, and so on. At the same time, a central part of COVID response has been keeping “essential activities” of the economy operating in the context of a health emergency. This also is a matter of governing circulation, ensuring certain kinds of circulation while suppressing others. These practices for governing circulation cannot readily be understood either in terms of the self-adjustment of the economic system or, on the other hand, in terms of a governmental takeover. Rather, resilience, as a mode of governing circulation in emergency situations, divides up the political and the economic in distinct ways.

This focus on circulation – again as a register of governmental knowledge and practice, and not as a second-order analytical category – also offers a distinctive kind of critical purchase on key terms of contemporary government. I have written on this point in relation to neoliberalism, but here let me indicate what I mean by staying with this example of resilience. Some scholars have traced contemporary resilience to particular thinkers like Hayek and Holling, and then arrived at a broad diagnosis – that, for example, resilience is a program of dealing with shocks and crises through laissez faire of some distinctive contemporary variety that is worked through the post-war information sciences. To my reading such analysis commits a sort of genetic fallacy in finding essence in origins. It also ontologizes the political and the economic, treating them as sort of primary categories of existence to which a governmental rationality like resilience assigns things. By contrast, a focus on circulation situates us at the level of practices, and concrete spatial and material arrangements, and allows us to consider how specific programs of governing divide up and thereby constitute the political and the economic.

As an illustration, some of my recent work has been on urban resilience planning, much of it focused on systems of circulation: water, electricity, finance, etc. In California, much of the population lives in arid or seasonally arid areas, and relies on vast circulatory systems that capture, store, and distribute water. But the balance of this circulatory system is threatened by growing extremes of drought and by warming temperatures that will reduce the size of the snowpack in the mountains, an enormous stockpile of water that allows this system to deal with inter-seasonal variations in rainfall. So, water supply is a key vulnerability that many urban resilience and adaptation plans address. For example, Los Angeles has recently developed a plan to localize the water system. This plan proposes to build hundreds or thousands of green infrastructure installation – rain gardens, bioswales, other permeable treatments – to recharge a massive aquifer under the city. The idea is to create a closed loop of rain and stream capture, storage, consumption, and treatment within the metropolitan area to reduce the city’s exposure to the disruption of large-scale circulatory systems, and better able to deal with local rainfall variation.

This proposed system of circulation interacts with choices of all kinds of market actors –both individuals and firms. But it constitutes the adaptive transformation of this circulatory system as first of all a site for government intervention and collective action. It thereby frames a whole series of political problems – structures a political terrain. What benefits or costs will be entailed by the installation of green infrastructure elements, which are at once part of a large circulatory system and interventions in a particular place, with local costs and benefits? How will these be distributed? How does this system of circulation map on to political jurisdictions? Who is in and who is out? What would it mean if a massive urban area like L.A. seceded in large part from the California water system, in which urban users cross-subsidize rural users, mostly to the benefit of large-scale agribusiness? Once we free ourselves from trying to find the hidden workings of a radical market project or whatever else as the deep truth of resilience initiatives, and instead focus on the level of practices and particular spatial and material arrangements, innumerable specific sites of politics and very concrete political stakes come into focus.

Bevorzugte Zitationsweise

Die Open-Access-Veröffentlichung erfolgt unter der Creative Commons-Lizenz CC BY-SA 4.0 DE.