Open Science and Open Media Studies

Questions on a culture in transition by Jeroen Sondervan

Open Media Studies as a term or concept is obviously not isolated. It comes out of a larger international debate on new developments around research and publishing practices in a digitized and open environment, often referred to as «open science». However, what exactly is open science? More precisely: what is Open Media Studies? For me this is a question with no definitive answer. Moreover, I think we do not need one.

Open science as a collective term stands for many things; open access to publications, open research data, open source software, research tools, open peer review, open hardware, open citations, etc. In short: these are all results of practicing «openness» within the entire research cycle, considering values and principles defining what could possibly be the best way of doing this. Needless to say, that for every researcher this could mean different things.

For the humanities and to a lesser extent the social sciences, the term open science is somehow problematic. It implies a direct relation with the (natural) sciences and that indeed is the area where these practices indeed are much stronger developed. However, research practices in the sciences are incomparable with practices in the humanities (and social sciences). Not to mention the differences in publication cultures. For almost all disciplines in the humanities, it is about the art of rhetoric and argumentation to reflect on and debate culture, cultural production, society and people’s behaviour, resulting in long articles, and books, based on original sources and/or historical data. Open access, reuse and transparency of research practices, data and publications will probably mean a different thing to a physicist than it will to a media scholar.

In many current discussions however, and I hear this from researchers as well, the focus is on Open Science. This is problematic in my opinion. The terms open scholarship or open research are more inclusive in this context. Nevertheless, every term has its limitations. Open science might leave out the «scholarly» approach. Most (citizen) scientists outside academia do not consider themselves as scholars and would probably feel uncomfortable by using open scholarship. Similarly, open research leaves out education.

At the risk of being bogged down in a never-ending semantic discussion, I hereby just want to state that it is not as simple as one might think and there will not be a one-size fits all solution. However, there should not be two separate worlds. There is much to learn from each other. Are humanities lagging behind? No, and I think media studies in particular is not lagging behind and it would be worthwhile if we look at existing best-practices in opening up research in media and communication studies and ask ourselves too what we can learn from what is happening in the sciences.

In 2015, colleagues Bianca Kramer and Jeroen Bosman from the Utrecht University Library started their 101 Innovations in Scholarly Communication project. In this project, they commenced a survey amongst more than 20.000 scholars worldwide. The landscape of scholarly communication is constantly changing and the changes are driven by technology, policies, and culture. However, in the end, the researchers themselves are the ones using tools and software in order to produce science and they are adapting constantly to new standards. Kramer and Bosman started the survey in order to create an overview of all these tools used for research, writing and publishing.

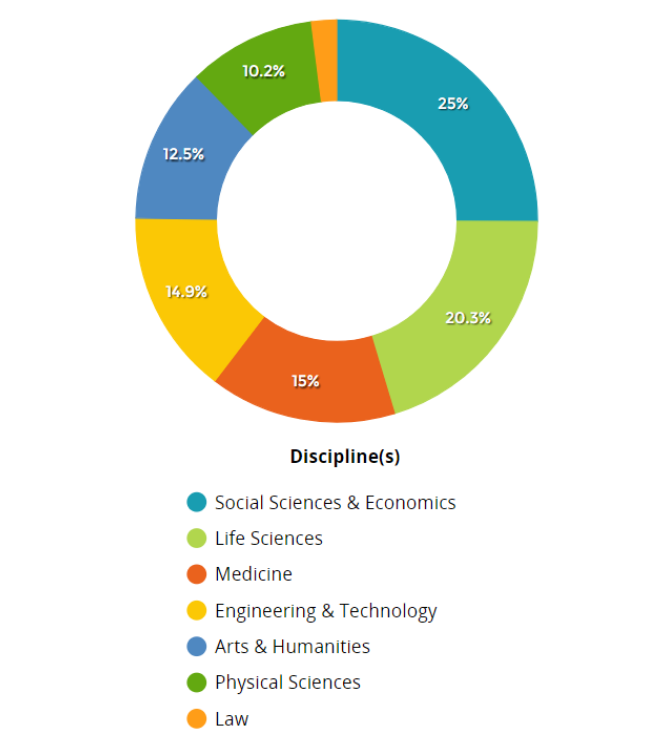

Fig 1. Respondent’s demographics: discipline(s) (https://101innovations.wordpress.com/survey-results/demographics/)

From this survey we can learn a lot about the use of research practices and tools but it is striking that only 12,5% of the respondents were from the humanities. Only a very small portion of this percentage had a background in media studies. For further discussion, it would be helpful to work on collecting more data about open access and open science practices in media studies.

How does media and communication studies fit into this?

Back in 2006, when I started at Amsterdam University Press (AUP) as a publisher, literally almost not a single author I talked with had heard of Open Access. This of course is only part of the truth, since we have seen important developments in that period with the launch of, amongst others, MediaCommons (2006), University of Michigan Press’ digitalculturebooks project (2006) and a bit later the community blog Film Studies For Free (2008). Open access was on the minds of media scholars but at that time very much isolated and mostly driven by individual frustrations with the traditional publishing system. In recent years, however, there has been a growing number of scholars experimenting with new ways of publishing their research (e.g. Lev Manovich, Kathleen Fitzpatrick, David Gauntlett, Miklos Kiss) using iterative writing and new online publishing formats.

Meanwhile, discussions about the issues of access to academic literature were mainly held between libraries, funders and (science) publishers. In 2008, together with five other European university presses, AUP started the OAPEN platform for depositing and disseminating open access monographs. At that time, it was one of the first online platforms for publishers to give and for readers to get access to academic books. Today over 120 publishers worldwide are depositing their books on the OAPEN platform. They have reached over 6,4 million downloads (counting started in 2013) and the collection of media and communication related books is growing steadily. The Directory of Open Access Books indexes over 140 open access books tagged as media studies. The Knowledge Unlatched project, a service to support open access books, and which started in 2014, offers a media & communication studies list and helped to «unlatch» 31 books in open access with financial support from libraries. More than 190 full open access journals are tagged under communication and (mass) media studies in the Directory of Open Access Journals. Impressive numbers over the years, but if you think about what the yearly global output of scholarly articles and books in media studies is, there is only one conclusion: open access in media studies is still in its infancy.

Scholars unite!

All the above examples are wonderful but if we want to move forward more quickly we need to change the way we think about (the culture of) publishing. In his article from 2016, «Open Media Scholarship: The Case for Open Access in Media Studies», Jeff Pooley argues that «media and communication scholars should be in the forefront of the open access movement». One of his arguments is that «the topics that we write about are inescapably multimedia, so our publishing platforms should be capable – at the very least – of embedding the objects that we study».

I would like to add to this that we not only need platforms and publishing models that are robust, sustainable and capable of dealing with (old and new) multimedia formats but we also need to think about how do we connect publishing infrastructure(s) and (multimedia) archives in a sensible way? We need a better sense of interoperable (open) infrastructures and metadata to connect online publications to archives and audio-visual source material.

Another important aspect of advancing scholarly communication is to speed up the process of publishing journals and books in media and communication studies. The time between an article’s submission to a published version can take a very long time, sometimes even years. Review pressure is getting out of hand. Why are we sticking to this idea of a «final version», which is publishable? What if we change that thinking into: «it is not a version of record we need; it is a record of versions»?1

Pre-/and post-print publishing is almost non-existent in the humanities, and besides a few examples this is also true for media studies. Apparently, it is difficult to share research results before it is published in a journal or as a book. On the other hand, everyone seems to be eager to share their publications in different stages of their research in academic social networks like ResearchGate and Academia.edu. Why is it still not common practice in the humanities to share the work on a preprint server, comparable with ArXiv or SSRN, and new emerging disciplinary preprint servers? Lack of knowledge and fear seems to be an issue here. Creating awareness and discuss the potential benefits and pitfalls of pre-publications with the media studies network is essential here.

Now research councils are taking position

This academic year started with big news on open access. On September 4th Plan S was presented by a coalition of 11 national research funders (the German DFG is not one of them) supported by the European Commission. After the launch, people supportive of open access reacted positively: finally, something will happen and this could lead to a breakthrough! Publishers on the other hand immediately started their engines to counter the announced policy of the coalition. But what exactly does Plan S entail? Current (online) discussions are mostly held between funders, publishers, librarians and open access advocates. What are the implications of Plan S for the humanities, and more specifically media studies?

The easy explanation: from 2020 onwards, all research output funded by one of these 11 research councils needs to be published in open access under a CC-BY license and without an embargo period. One of the more challenging parts of the plan is the rejection of hybrid open access journals (subscription journals that allow authors to pay for freeing up their articles). To give an example of what this could imply:

Taylor & Francis has 2.300+ hybrid journals. 95 of those journals have media in their title and are in the hybrid journal portfolio. If you as a researcher want to publish research funded by let’s say the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO), all those journals currently do not comply with the set of principles stated in Plan S. So you aren’t allowed to publish in any of those journals.

This raises of course many questions: How will (existing) publishers react to Plan S? Will they change their existing hybrid journal portfolios and current open access business models? Will there be enough other options to publish your work? What does this all mean for my career path and me as a researcher? Moreover, a much heard comment: how does this relate to the academic freedom (and comments) to publish where you want? The immediate implications for media scholar are likely to be small, since the majority of research funded by these research councils is in the sciences. However, the above questions will get more pressing when this coalition and the principles get a broader support (e.g. universities).

Up to now, most of the researchers’ responses are from the sciences. As far as I’ve seen there are only a few responses from humanities researchers about what this policy could mean for researchers in general, academic freedom and for open access books but more are very much welcome.

A closing remark

Addressing some of the pressing issues in a rapidly changing and evolving world of scholarly communication, illustrates how these changes have affected media scholars so far, and raise several more questions. I hope it can lead to a broader discussion amongst media scholars (and networks like GfM, NECS and SCMS) about how we would like to see in which direction the culture of Open Media Studies needs to go.

For further reading and information on open access policies, funding and publishing in media studies: www.oamediastudies.com

- 1Credits to my colleague Bianca Kramer for using this quote.

Bevorzugte Zitationsweise

Die Open-Access-Veröffentlichung erfolgt unter der Creative Commons-Lizenz CC BY-SA 4.0 DE.