Screenshot of the website from Arsenal Berlin - temporary online cinema (21 May, 2020).

Abruptly Altered Horizons

On Covid-19, Momentous Events and a Not so Rare Phenomenon in Historical Reception Studies

Weeks and months of lockdown have limited our vistas, constricted our horizons, confined our worlds: where borders had been abolished, fences were re-erected; where mobility had been taken for granted, people were forced to accept stillness; where openness had reigned, doors were closed and gates remained shut. At the same time new openings became available: as if to counter the myopia inflicted on us by the virus, some institutions have lent us new lenses to the world. Although this stirred some controversy, cinematheques, film museums and festivals in Munich, Amsterdam, Berlin and many other places have made treasures available for free to everyone with a working Internet connection (see image above). Although it has yet to be analyzed in depth if this decision has lowered institutional barriers (intimidating as they may be for some) and functioned as an open sesame for new audiences, I find this thought far from implausible. Let’s face it: how much Netflix can you swallow before you choke? In our private prisons the term ‘escapism’ gained new meanings and the old Cavellian adage of the world viewed 1 from behind the barrier of the screen acquired new urgency. The newly opened spaces of these film institutions allowed for altered horizons.

But our horizons changed in a different way as well, as perceptions and interpretations were closed in one way, while opening up in other ways. Just think of how, since the onset of Covid-19 and social distancing, the way spectators perceive filmic space and character behavior has changed dramatically. What may have looked innocent once, now appears dangerous. What didn’t raise attention in pre-Covid-19 times, is all of a sudden perceived with heightened tension and alertness. This is a point media scholar Kyle Stevens and film critic Susan Vahabzadeh have lifted from the level of subconscious awareness to full-fledged recognition, making many of us exclaim «Yes, that’s exactly how I have been looking at films recently as well!» As Stevens confesses: «When watching movies, I have lately found myself wincing ever so slightly at people dancing in clubs or of a friend running up to another in the street for a hug.» Similarly, Vahabzadeh squirms when seeing masses of spectators gather at a race track in a film such as James Mangold’s Ford v Ferrari (2019): «Currently, there seems to be a shift in codes; things have a very different meaning, and very normal scenes all of a sudden seem to come from a horror film,» she writes in the Süddeutsche Zeitung.

Inversely, what might have been read as an index of social alienation – like the characters standing far apart in the famous Nymphenburg Palace shot in Alain Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad (1961) –, all of a sudden feels like a perfectly reasonable, even responsible way of positioning oneself in space. Or think of a formerly sinister object Vahabzadeh mentions: While the mask in horror films and crime movies usually connotes danger – think of Jason in the Halloween franchise –, it becomes a benign object in our contagious times.

This sudden shift in how we perceive and interpret movies seems remarkable. Using the term «horizon», which has roots in Husserl’s phenomenology, Gadamer’s hermeneutics and Jauss’ reception theory, we could refer to it as the abruptly altered horizon. Yet this phenomenon isn’t all that rare, and it becomes all the more common the closer we look at it.

Dunkirk and Its Brexit Reading

Consider Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk. When the film arrived in cinemas across the globe in summer 2017, in what from today’s perspective seems to be a temporal galaxy far, far away, reviewers were quick to point out that the World War II film had a strange resemblance to the present: Was the case of the British soldiers brought home and rescued from the threat on the European continent not reminiscent of the referendum, from the previous summer, to leave the European Union? Had Nolan made a Brexit film, German critic Tobias Kniebe asked head-on in an interview with the director for the Süddeutsche Zeitung Magazin?

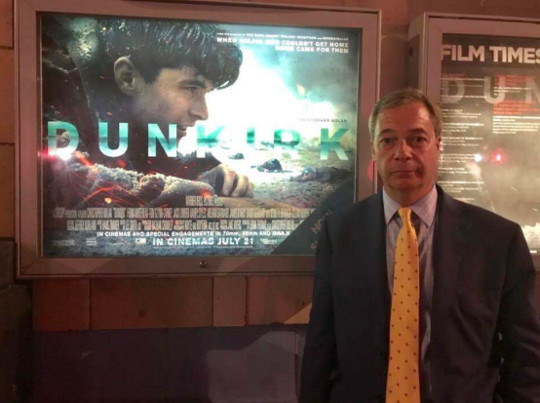

Even right-wing Brexiteer Nigel Farage turned into a veritable film interpreter and tried to capitalize on what could be read as a glorious move to save the United Kingdom: «I urge every youngster to go out and watch #Dunkirk,» Farage tweeted on July 26, 2017.

Screenshot taken from Nigel Farage’s Twitter account (21 May, 2020).

Christopher Nolan soon rejected this thematic proximity: «Interpreting the events of 1940 through a modern lens,» he said, «is frankly disrespectful to the people who lived through the real-life events. This is something that happened in 1940, not something that’s happening in 2017.» Claiming that a film like Dunkirk was years in the making, Nolan continued: «Brexit happened while we were shooting and was as much a surprise to us as to everybody else. […] As a filmmaker, you can’t control the world that your film goes out into.»

Indeed: important historical events – catastrophic just as much as emancipating ones, traumatic as well as redemptive events – can abruptly change the audience’s perceptual and hermeneutical horizon. To use Nolan’s metaphor, the film is seen through a different lens with the onset of a ground-breaking historical event. The film becomes part of a different discourse and may be interpreted in ways entirely unintended by its makers. Of course, this does not mean that the general openness of interpretation is foreclosed and audiences are forced to view the film in a certain way. It simply becomes more likely.

9/11 and Noises Louder than a Bomb

As a third example, we could cite the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on September 11, 2001. The reactions to Hollywood films like The Sum of All Fears (2002), Collateral Damage (2002), Bad Company (2002) or Spiderman (2002), which were planned and shot long before the terrorist attacks, were discussed by many critics precisely in their light.

Screenshot of Stephen Holden’s New York Times article (21 May, 2020).

Stephen Holden, for one, in his New York Times review of Phil Alden Robinson’s Tom Clancy adaptation The Sum of All Fears, begins his article by claiming: «The Sum of All Fears, which imagines the detonation by terrorists of a nuclear bomb on American soil, couldn’t have been better timed to coincide with the country’s jittery mood. It was just days ago that United States officials suggested that suicide bombings are inevitable on American targets. And as the film’s fictional depiction of events leading up to a small nuclear blast (in Baltimore) unfolded at a recent press screening, the audience sat riveted in silence. It’s a striking measure of the nervousness of the country right now that a movie so full of holes should be as gripping as it is.»

Like Nolan, Holden, too, mentions that the film was begun well before 9/11. The film, he writes, «seems at once old hat, insufficient and foolish.» And yet he cannot resist watching the film against the backdrop of 9/11. He ends the article by warning: «The inadequacies of The Sum of All Fears, in the light of Sept. 11, suggest that if the political thriller is to remain a vital genre, a new, toughened-up realism is necessary. Neo-Nazis [who are behind the global coup in the film] no longer suffice as villainous sitting ducks, and Hollywood may finally have to come to grips with the real issues that can’t be reduced to black-and-white caricatures.»

Above I have used a (somewhat stereotypical) visual metaphor to describe the phenomenon when I spoke, with Christopher Nolan, of looking at the film through a new lens. With literary scholar Wai Chee Dimock we may also privilege an aural metaphor and talk about an unusual noise that changes the viewer’s perception. Dimock, in her widely cited article “Theory of Resonance,” writes: «Noise includes all those circumstances that complicate readers’ relations to a text: circumstances that, filling their heads and ringing in their ears, make them uninnocent readers, who encroach on the text with assumptions, expectations, convictions. Noise includes all those circumstances that so quicken the pulse, so sensitize the interpretive faculties, as to call forth unexpected nuances from words composed long ago.»2

At the time, the crash of the planes and the collapse of the Twin Towers created an interpretive noise louder than a bomb. When people woke up on the morning of June 24, 2016, the day after the Leave-Remain-referendum, the results produced a stunned silence whose aftereffect was extremely loud and felt incredibly close. Not least, when the effects of the current pandemic were gradually dawning on us (on some notoriously later than others), we began to watch the images and listen to the sounds of films differently: being physically close started becoming a threat to characters we sympathize with, and hearing the sound of silence – which in horror films is often a mark of dread and in modernist filmmakers like Ingmar Bergman becomes anxiety-infused – all of a sudden was felt as a relief. In the words of cognitive film theory: our interpretive schemata were exchanged – exchanged with an unusual suddenness.

Bevorzugte Zitationsweise

Die Open-Access-Veröffentlichung erfolgt unter der Creative Commons-Lizenz CC BY-SA 4.0 DE.